By Morf Morford

Tacoma Daily Index

Politics is the art of the possible, the attainable — the art of the next best. – Otto von Bismarck

No one should see how laws or sausages are made. – Anonymous

There is no experience like seeing your local political representatives doing their jobs.

Their job, to put it simply, is to represent us – their voters, their citizens, their constituencies.

On any give issue, “stakeholders” can be any of us – with the Orwellian subtext (from Animal Farm) that, though stakeholder voices may be equal in theory, some “are more equal than others.”

The City Council of Tacoma has been reconsidering an extension of Tideflats Interim Regulations.

These interim regulations were initiated in May of 2017 and adopted for an initial one-year period as of November 21, 2017.

This interim was to concern new industrial uses, new residential development (on the slopes above Marine View Drive) and some new heavy industrial uses.

The emphasis in all these was the word “new.”

The Port of Tacoma is inherently a “working waterfront.” Tens of thousands of workers are employed at our port. Many families have worked there for generations.

The Port of Tacoma is central to the identity, history and economy of Tacoma, Pierce County and the greater South Puget Sound.

You could argue that every citizen and resident, every tribe and people, every worker, every union, even every species based in the southern Salish Sea and in the shadow of Mt. Rainier is a “stakeholder” in this urgent, immediate and semi-eternal conversation.

How we use the Port, and how we leave it for future generations will, for better or worse, be the legacy we will be known for.

Previous uses – and users- of the Port have left us – the continuing residents of Tacoma – with costs and toxic remnants of careless extractive technologies.

Many of us remember, even as we struggle to forget, the (sometimes literal) burning sting of the “aroma of Tacoma.”

Some defenders of that sulphurous toxic haze described it as “the smell of money.”

It was “the smell of money;” it was the smell of residential home values and local business investments turning into smoldering ash in front of our eyes.

As Seattle – and Bellevue – and other areas expanded into world-renowned centers of commerce with businesses like Microsoft, Starbucks, Amazon, Boeing and many more, Tacoma languished with its (well-earned) reputation as “the armpit of the northwest.”

Tacoma had ASARCO and suffocating pulp mills. Seattle had a world’s fair, Boeing, and it seemed, the future.

Tacoma, back then, seemed locked in a dirty, industrial, toxic past.

Much has changed in the past fifty years or so – even the past two or three years – in Tacoma.

Laws, guidelines and community expectations have literally changed the landscape of Tacoma.

Those of us who grew up in the grimy wasteland of Tacoma would never wish to go back there.

And those who have no memory could not even begin to imagine a world as literally forsaken as Tacoma – especially its waterfront – barely more than a generation ago.

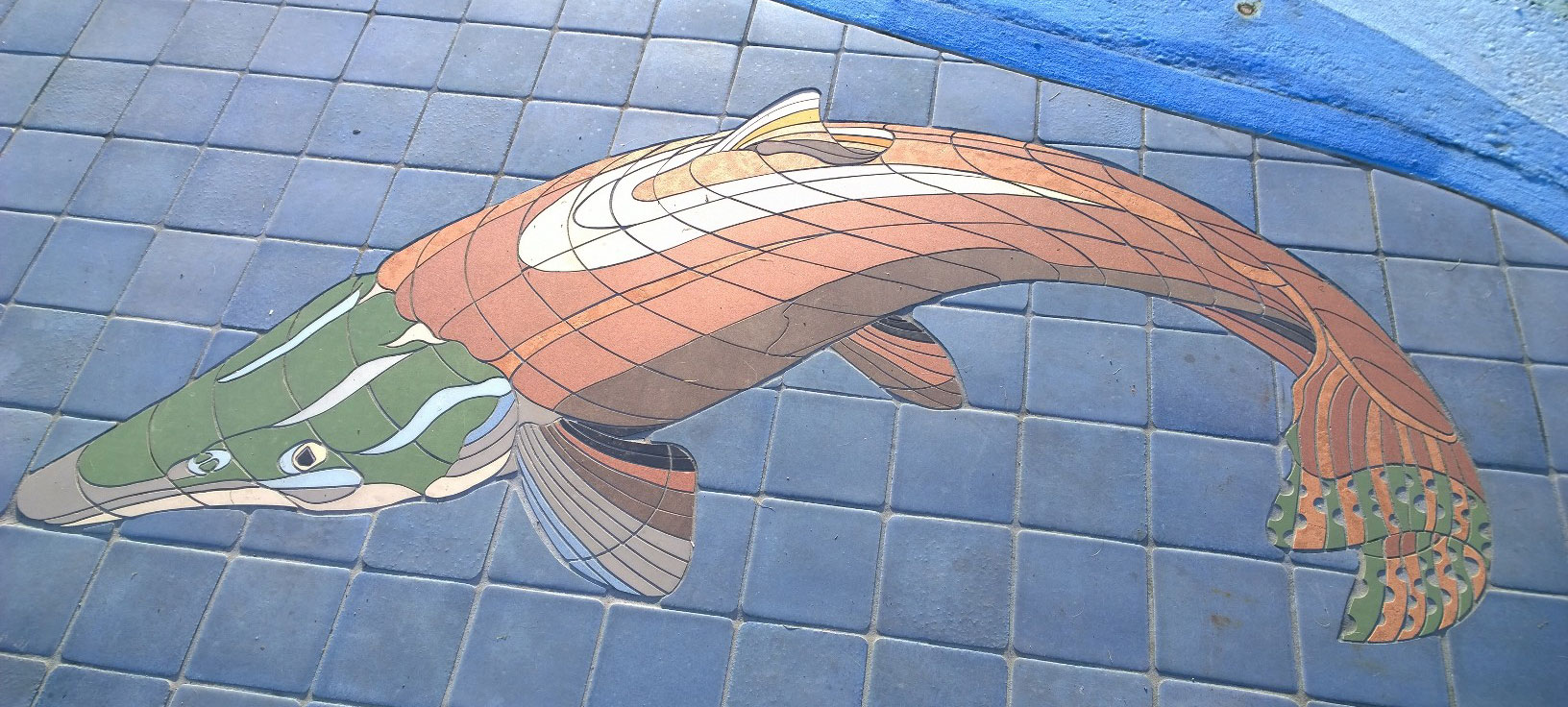

I take my grand children on walks along Ruston Way and Point Ruston.

I don’t even bother telling them that they are also walking on Superfund toxic waste sites.

It took years of vision, lobbying and hard work to wrest a beautiful corner of Tacoma with stunning views of the Olympics, Mt. Rainier, The Cascade Range and Commencement Bay from the crumbling, poisonous ruins of lead and arsenic encrusted lunar-landscape.

There were those back then who argued that it couldn’t be done – that Tacoma was an industrial city, with a culture and economy rooted in soot, sweat and brute force.

“You can’t eat scenery” was a saying back then. “Who needed clean air or water if the money was good enough?”

It turned out that every living thing – from people to salmon, to the ever-present fir trees – needed clean air and water. And the money was never enough. And never could be.

Many individuals and companies took their profits and left town.

Some of us, individuals, families, companies and tribes stayed. We lived, and eventually began to thrive, in spite of the toxic dregs left behind, the snide comments and the soiled reputation of the place we love.

There are few things we, as long term residents, we with roots deeper in our community than we can even recognize, know more than anything; Tacoma can be, and will be, better. We may flounder and meet obstacles that seem insurmountable, we may even appear to give up, but we know, more than we now anything, that Tacoma’s best days are ahead of us.

There is no going back. The job vs environment argument is completely bogus. We have had, and we will have, both. We demand both.

We will also have a community, a place, an identity worth preserving, worth fighting for.

As I listened to the public hearing on the proposed extension of the tideflats interim regulations, I was struck by the fact that each group, for or against the extensions, expressed their love for Tacoma and their hopes for a prosperous future.

Some sounded rehearsed, polished and crafted, others were passionate and spontaneous.

Some had the feel of a corporate boardroom focus group, others spilled out like a desperate cry.

What struck me on my way home was that we are all stakeholders, we are all participants in a decision we will live with for generations.

On my way home I thought of that term, the term that perhaps more than any other defines us – as Americans, as citizens, as those with a local voice that cares about immediate local issues with lingering impacts on future generations; E Pluribus Unum.

From the many, one.

We come from many places, we have may different concerns, values, priorities and experiences, but we are here, together. We share this place, this name, this identity.

The real question is where we go, after this, or in fact, any decision, is made. Do we trust each other? Do we trust our political process?

Can we go on in the confidence that our values, our voices and our identity are all respected and that a generation – or two – from now, they will look back and be thankful that we made the best decision with them in mind.