Are we a nation of laws and not of men?

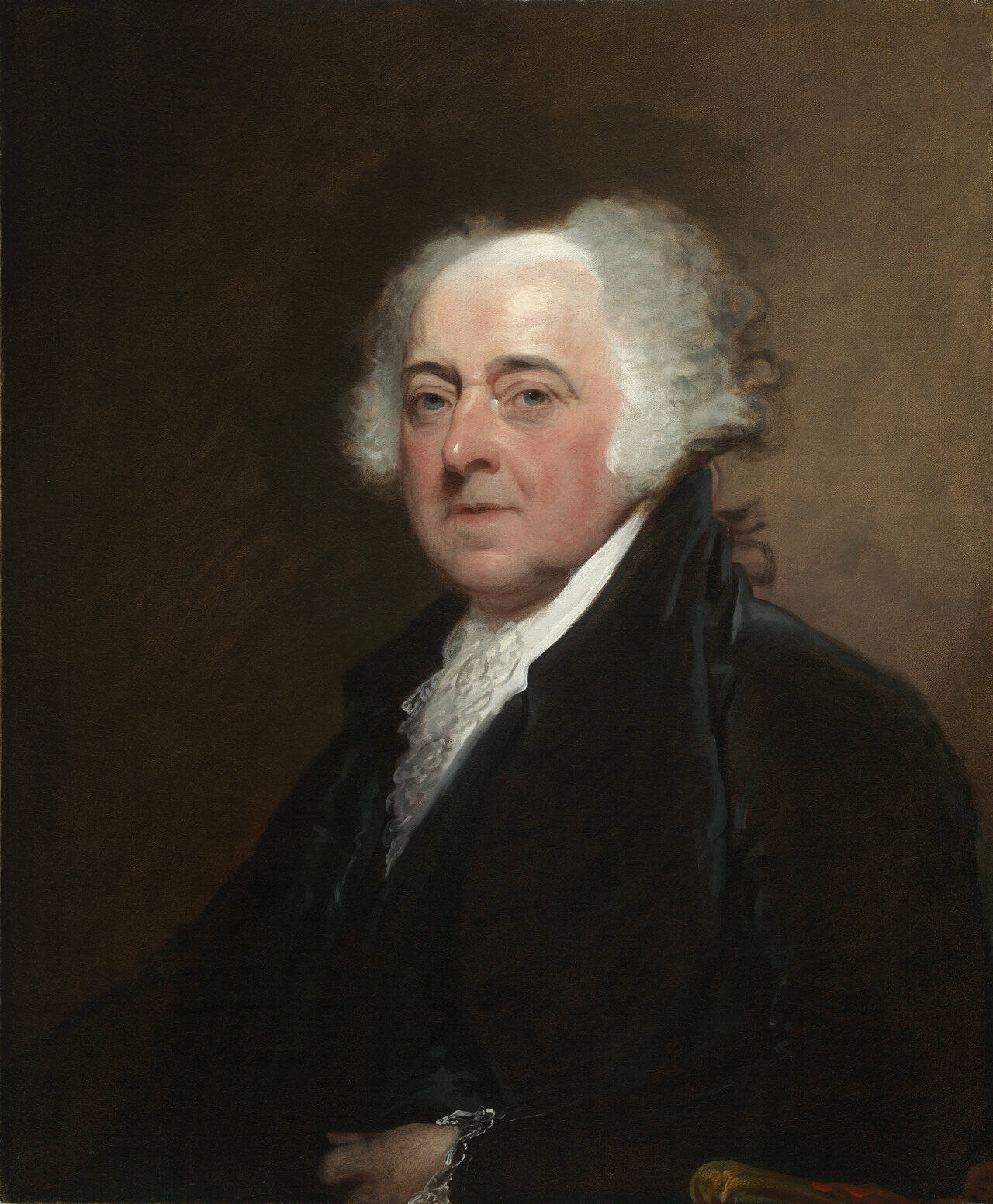

American Founding Father and second U.S. President, John Adams, famously included this concept in the 1780 Massachusetts state constitution.

This simple phrase emphasizes that our society is governed by laws, not, as one historian put it, “by the whims or personal judgments of individuals”.

This premise, that every one of us stands equal in the eyes of the law, has been a core premise of our nation since the very beginning — and one that, deliberately, set us apart from dynasties and untrammeled power and impunity of kings and royal families that dominated, and often exploited the resources and individuals of their own nations. And, of course, these same “royals” initiated wars and imperialistic pursuits out of vanity, greed and a search for something approximating enduring fame.

The premise of being a nation of “laws and not men” could not be more simple; everyone, regardless of their position or status, must adhere to the same legal principles.

Our cultural and national identity and unity doesn’t emerge from our ethnicity or religion, or income, or status but in the shared belief that we are free and autonomous men and women who govern ourselves under a shared understanding of the (relatively) unchanging and objective rule of law.

You may have seen statues or other portrayals of a figure, blindfolded holding the scales of justice. It is often seen in courthouses or other legal settings.

The idea is that justice, to mean anything, must be based on evidence — not on appearance, status or influence.

Every distortion of this premise, from bribery and corruption to legal immunity based on position or wealth has been clearly, even universally understood as a violation and affront to the deepest, and most firmly held values of our nation.

From the very beginning, the whims, corruptions and atrocious actions of the Old-World monarchies have been exactly what our Founding Fathers, and most American office-holders (and certainly most citizens) have (literally) rebelled against.

We, in the United States are independent, autonomous citizens, not “subjects” and we, each one of us, is a working, essential aspect of the “republic” (as opposed to a monarchy) that many before us have given their lives and dedicated their energies to protecting and preserving.

As our Founding Fathers knew all too well, the ultimate ideals and promises of America — individual expressions of life, liberty, and property are threatened if not endangered by anyone, of any office or status having any kind of unlimited legal immunity.

One of the ironies of the recent conversations about legal immunity for a head of state for the USA is that no previous president ever requested it or aspired to it, and of course, the only person, president or otherwise who would need to request such immunity would only be someone who intended or had already engaged in criminal activity.

To put it simply, such an appeal goes against everything America has always has ,and I hope, always will, stand for.

We have a long tradition of considering our political office holders not only as public servants, but also, in almost every way, representatives of each one of us, with rights and privileges no less, and certainly no greater, than any of us.

George Washington, considered by many of almost every political persuasion (perhaps because he was not associated with any political party of his time — and, in fact warned against such an eventuality) left office, as anyone in authority should, quietly and to his private own life at the age of 65.

In the face of many appeals to stay in office, Washington’s left office gracefully.

Washington’s greatest adversary was almost certainly Britain’s King George III.

After the war with the Colonies, the king asked his American painter, Benjamin West, what Washington would do after winning independence, presuming of course, that Washington, like every would-be king or dictator would claim and refuse to relinquish any power or authority, West replied simply, “They say he will return to his farm.”

“If he does that,” the astounded monarch said, “he will be the greatest man in the world.”

George III knew, far more than most, the depth and deception — and destructive capacity of corruption, nepotism and exploitation — and, of course, the culture of obsequiousness and craven “yes-men” inherent in such a system — he knew where true human greatness lies — in humility and by honoring laws and authority — not in flaunting one’s immunity from the demands and obligations of basic decency.

George Washington’s Farewell Address holds, toward the end, his hopes that his words would — “moderate partisan rivalry, warn against foreign intrigue and guard against pretended patriotism” in the full knowledge that “given human nature and the usual course of nations” his advice was not likely to have the impact he intended.

He also warned of the inevitable pernicious effects of any two-party political system.

Perhaps in this, possibly the most contested and conflicted election of our nation’s history, we might reflect on who we were, who we are and what we are becoming.

There might be no greater way to honor our presidents and our own national legacy.

My suggestion is that President’s Day should not be a time for honoring any particular president, but instead, the whole of idea of president, what sets it apart from the concept of king, dynasties or royalty. The premise of our system is that, not only can anyone become president, but that at every level, the president is, in fact, one of us, and also at every level, represents us and our best interests -and, one would hope- our best selves.

Our ideals may, in all too many cases, may be aspirational, with glaring failures and shortcomings.

But our ideals are what are written and, to a large degree, believed and shared — our lapses could easily be seen as departures from our intentions.

Our system is premised on the values of fairness and opportunities, with, as we all “pledge” “with liberty and justice for all”.

This is, by any historic standard, a high bar, but that is the point — and it is what we all, at our best, should be aiming for.