For local architects and history buffs, the six-story, 118-year-old Luzon Building downtown is a jewel.

Designed by Chicago architecture firm Burnham & Root, it was one of the first high-rise towers on the West Coast, the embodiment of engineering genius sturdy brick shell, cast iron columns, and wood construction on the upper floors — that allowed the building to top out at a soaring height for 1890s Tacoma. It was an engineering model that would be copied, and opened the door to the future development of skyscrapers.

For drivers speeding down South 13th Street toward the Interstate 5 onramp, however, it’s something else: a dingy building that resembles a decayed tooth more than an architectural marvel. Decades of neglect have left the building in a sad state. A size-able tree grows out of one broken window, steel fire escapes appear brittle, and pigeons rest on window ledges.

It has been the subject of on-again, off-again development rumors for at least the last five years. The latest hope for the Luzon Building comes from downtown Tacoma-based Gintz Group, which purchased the building in March and plans to convert it into Class B leasable historic office space. In the end, the company will have spent $7.5 million on purchase and renovation of the building.

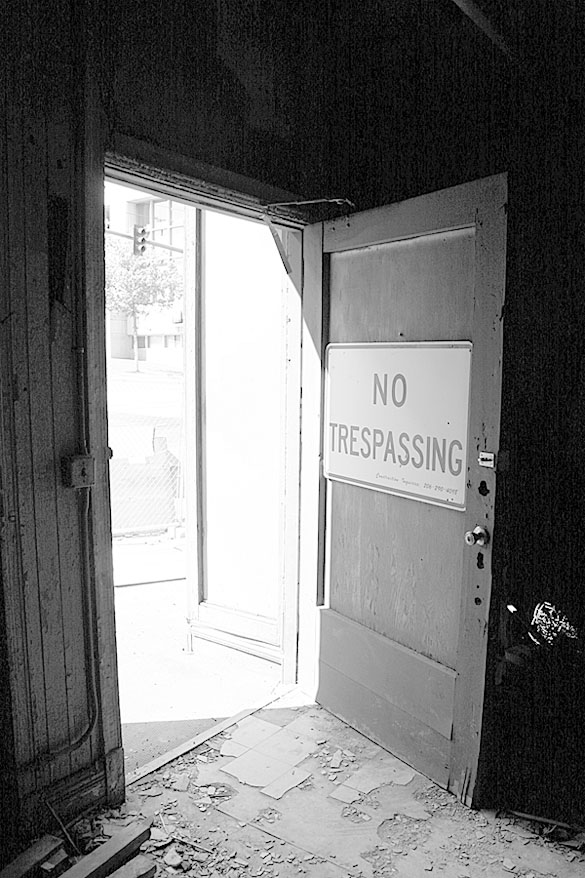

This week Gintz Group project manager Tim Lieberman unlocked the doors and invited the Tacoma Daily Index inside to take a tour.

“I haven’t lost anybody yet,” joked Lieberman, as a flood of sunlight poured into the Commerce Street entrance and a large moth darted toward sunlight.

Inside, it was not unlike the “Fight Club” house: paint peeled from most surfaces like skin off a week-old sunburn; holes large enough to crawl through existed in some of the walls; water dripped from too many places to count; and a sheen of dirt covered most windows, affecting a misty glow on most floors. In many areas, floors sank like whirlpools stretching down to the next level. Above us, ceilings comprised of central beams with rib-like planks bowed like giant rib cages.

Despite all the neglect, the building has charm.

A 1916 Otis elevator will be restored. “ThyssenKrupp’s modernization team is going to take the elevator offsite, fully rehab it, and then rebuild on top of a brand new plaster,” Lieberman explained. “All the controls and machinery will be new. But when you walk into the elevator here, you’ll be walking into a historic car.”

And its prescient design still affords benefits: when completed, tenants will have a whole floor — some 3,300-square-feet — with large windows offering great natural light on three sides.

Contrary to some reports, says Lieberman, the first floor and basement aren’t flooded. “There’s no water down there,” he says. “Someone said there was a stream flowing through there. That’s a myth.”

Today the project hinges on a federal tax incentive that could total $1 million toward the overall project. According to Lieberman, the application was submitted to the Washington State Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation last week. The department has 45 days to review it. If approved, the application will then be forwarded to the National Park Service for a similar 45-day review.

The company hired Artifacts Consulting to complete the application, and Lieberman is confident both reviewing bodies will recognize the company is taking preservation to heart in its development plan.

The biggest potential hurdle? Constructing a new stairwell on the outside of a building that is listed on city, state, and national historic registers. It’s not unprecedented: the same thing was done at historic Albers Mill on Tacoma’s Thea Foss Waterway.

If the application is approved, the company would start the renovation in January. From there, it will take approximately one year to complete.

The Index asked Lieberman a number of questions. Here is what he had to say about the project:

TACOMA DAILY INDEX: When people talk about the Burnham & Root design, it’s often about the type of construction used in building the walls and foundation. It’s a very unique building, correct?

TIM LIEBERMAN: In this particular case, what makes it so unique is the integration of steel into the building structure. The bottom three floors have cast-iron columns, which is what you see here, and then it transitions into a fully wood structure upstairs. That building type allotted them to build taller than anyone else. For 1891, it was revolutionary. By the turn-of-the-century, it was commonplace. You saw buildings that were much taller than this one. They had much more integrated steel structure. This is a building that has a massive exterior brick wall. It’s massive. Unlike other buildings, rather than stepping back at each level, it is actually tiled. You’ve heard rumors the building is leaning. It’s not actually leaning. The brick is set at an angle.

INDEX: Being inside, we can see ceilings sag and can feel floors sink with each step. What is the extent of the damage to the building?

LIEBERMAN: Well, the building hasn’t had a good roof on it in 30 years. When it was owned by Pierce County, they didn’t maintain it. What has happened is the roof drain is completely separated from the roof. The water has just been flowing into the building for 30 years. That is the damage you see right now.

INDEX: What other things? Is it still structurally sound?

LIEBERMAN: It is not. No. That’s one of the reasons we’re tearing everything out of here. What’s in here now has been subjected to so much moisture, we’re not comfortable repairing the sagging floors, and even what we’re standing on right now. The condition of the wood in the beam pockets, where it enters into the base of the wall, we’re just not comfortable marketing it as a Class B historic project with any of the existing internal structure.

INDEX: How close is this building to just collapsing in on itself?

LIEBERMAN: Not real close. The plywood floor diaphragm is pretty strong still. There’s no weight on the floors. Really what’s causing it to fall is the continuous water. It’s first rotted out and then pulled. Now it’s sort of hanging on this three-quarter-inch plywood. In the attic, there’s a beam that is broken and pulling on a wall up top. But I don’t believe we’re in danger of the structure collapsing.

INDEX: Is there any material, like old wood and beams, that will be re-used? Or will it be sent to a landfill?

LIEBERMAN: It won’t be land-filled. Most of what is here is wood. It will be taken out and shipped up and burned for electricity or turned into mulch. It’s not landfill-bound. I have posed the question of re-using the wooden floor joists, which are 2′ x 14′. It’s highly questionable how good they are because they have been so damp for so long, especially where they enter the brick.

INDEX: The windows are original?

LIEBERMAN: Yes. Dating back to 1891.

INDEX: When is the last time someone used this space?

LIEBERMAN: Early-1980s. There was the Fun Circus. There was a Chinese restaurant.

INDEX: What do you have planned for the renovation?

LIEBERMAN: This is a federal tax credit project, so there are parameters we have to follow. We’re saving all the windows. The cast-iron columns are being re-used in an architectural fashion and in their existing locations. They will still be here, you will see them there, but they won’t be doing anything. We have to keep the skylights upstairs. We’re renovating the the historic Otis elevator car, which is circa-1916 and in remarkable condition. That is pretty much it, other than maintaining floor height, ceiling types, material types, repairing plaster. Basically, this building will look like it did at the turn of the century.

INDEX: You mentioned Gintz Group has applied for a federal tax incentive. What is it?

LIEBERMAN: It’s a 20 percent tax credit that is applied to many of the soft costs of the job. Basically, 20 percent of the renovation costs can flow back in the form of cash.

INDEX: Do you think you will receive it?

LIEBERMAN: Absolutely.

INDEX: Have other similar projects gone through that federal tax incentive program?

LIEBERMAN: Albers Mill is similar to this one in that they added a new exterior structure to house their stairwell so they could meet fire code. We’re doing the same thing here.

INDEX: During a recent landmarks preservation commission, you mentioned the possibility of another building being constructed next door, and sharing the stairwell you plan to add to this building. What are the details of that plan?

LIEBERMAN: It remains to be seen if and how they can use it. However, we’re building [the stairwell] with knock-outs at each landing. There are two reasons [the stairwell] is where it is. One is circulation. The other is seismic — it’s being built to manage the seismic load of this building, as well as a portion of the seismic load from the new building next door.

INDEX: One complaint over the years has been, ‘When is this project going to get started?’ There seems to have been a a number of plans for the building, even before Gintz Group purchased it, that have started and stopped. Have you heard that question, too?

LIEBERMAN: Absolutely.

INDEX: What has been the challenge?

LIEBERMAN: The challenge for us is that we can’t do anything until our Part Two application, which is the federal tax credit application. It’s reviewed by the state historic preservation office — they have up to 45 days to review it — and then they kick it up to the National Park Service, which has up to another 45 days. So we have 90 days from the point at which we submit, at minimum, that we can break ground. That was something that early on we didn’t have a full understanding of. Any work we do now is at our own risk. If we do something and they say, ‘No, you shouldn’t have done that,’ then we lose the tax credits. The economics of the job are totally shot. What’s best to do, because our carrying costs are pretty low — the building wasn’t very expensive — is just to wait until we have that signed Part Two from the National Park Service and we know exactly what our project is.

INDEX: Have you run into any opposition from the state historic preservation office for wanting to build onto the outside of the building and attach a stairwell?

LIEBERMAN: It is always a concern. We don’t think we’re setting precedent. Albers Mill did it. There might be some sensitivity to the finish. I know the timing of the building to be constructed next door is important but not critical.

INDEX: Has the market been a challenge in developing this building, in terms of maybe having a more difficult time finding credit, and the economy not being as strong?

LIEBERMAN: Credit is an issue no matter who you are, unless you are putting all cash or a lot of cash into it. I would say this project is not unique in that respect. In terms of marketing, it’s difficult to tell whether or not this project is more difficult because it’s had so many false starts and people have been talking about it for 20 years and trying to figure out what to do with it, what’s good, and it never works out. My sense is that has hurt pre-leasing, for example. It’s hard to picture the project being completed when so many people have talked about doing the project. My gut is that once we break ground, things should pick up in the pre-leasing. We’ve shown it to a few people. Frankly, I don’t like to show projects like this at this stage. It’s very difficult for people to envision working in this. The nice thing about the building is that the floor plans are pretty small. We max out at 3,300-square-feet. It’s not like taking a chunk over at Wells Fargo Tower or some of the other buildings downtown and trying to carve out a little piece of a 12,000- or 15,000-square-feet floor. Here, you get a whole floor with windows on three sides, and you’re in a historic structure that is fully, seismically modern. It’s not a retrofit. It’s absolutely a brand new, seismically modern structure inside of an old shell.

INDEX: The Gintz Group has done several projects involving older buildings — their headquarters building on Broadway and the Mecca condominiums. How does this project compare?

LIEBERMAN: For this one, in some ways the tax credit makes it maybe a little bit harder. We can’t do everything we want to do. At the same time, we need that cash — it’s about $1 million tax credit. That’s the only thing that really makes this project worth doing. And that is barely worth doing, just from an economic perspective. There’s the glory of the building, giving back to Tacoma. Those are key components and we would never look at it purely from an economic perspective. But to answer your question, I would say this project is definitely harder. It’s definitely harder just to get through demolition. The demolition is very complicated and highly sequenced with shoring, a new core, a lot of steel ties it all together. When you walk in on the Pacific Avenue level after five or six months, you will see the sky. Literally, there won’t be anything in here. To have a building in that condition not fall is somewhat complicated and a little bit nerve-wracking. But once we start building the steel and concrete back up, it’s pretty easy. It’s a wide-open floor plan. We’re not building a ton of walls. It’s pretty easy.

INDEX: You mentioned pursuing the tax credit meant there were some limitations on what you could do with the building. What are the limitations? Did you consider renovating the building without preservation in mind?

LIEBERMAN: We have a responsibility, when you have a building like this, to do the right thing. We were going to do so much of what the Feds required anyway, there was no point in not doing it. The only thing the Federal money impacts is our ability to go up higher, which we would have done. I’ve done a lot of these buildings. This one, the windows are in great shape even though they don’t look like it. The underlying wood in the windows is in fine shape, so there’s no reason to kill it. A lot of developers would come in and rip out all the windows. There are ways to do this project cheaper, but you wouldn’t be doing the right thing.

INDEX: What did the Gintz Group see about the project that was do-able that other developers said wasn’t do-able?

LIEBERMAN: One of the things people tend to do with buildings like this is they tend to think they are worth a lot of money because they are cool. Even in this condition, it’s a cool building. They basically price the building out of the possibility of being renovated. I think Old City Hall is probably a good example of that, as is the Elks Building. This project, I was interested in doing it, the price was right just getting into it, and the tax credits made it sensible.

To read the Tacoma Daily Index‘s complete and comprehensive coverage of the Luzon Building, click on the following links:

- What’s Left of Luzon? Report keeps tabs on demolished building’s artifacts (Tacoma Daily Index, February 22, 2012)

- Sidewalk party marks Luzon Building demolition anniversary (Tacoma Daily Index, September 8, 2010)

- Burnham, Luzon Building featured in PBS documentary (Tacoma Daily Index, September 2, 2010)

- Year In Review: Luzon Building (Tacoma Daily Index, December 22, 2009)

- Luzon art show, fund-raiser to benefit Historic Tacoma (Tacoma Daily Index, December 16, 2009)

- Luzon’s Last Dawn (Tacoma Daily Index, September 26, 2009)

- Downtown’s Lost Block (Tacoma Daily Index, September 23, 2009)

- Luzon will come down Saturday (Tacoma Daily Index, September 22, 2009)

- Luzon’s Tough Lesson (Tacoma Daily Index, September 18, 2009)

- City will demolish 1890s Luzon Building (Tacoma Daily Index, September 15, 2009)

- Luzon’s Dark Legacy (Tacoma Daily Index, July 10, 2009)

- What Looms for Luzon? (Tacoma Daily Index, April 28, 2009)

- Luzon Unlocked (Tacoma Daily Index, August 28, 2008)

- Resolution would facilitate acquisition, renovation of Luzon Building (Tacoma Daily Index, October 29, 2007)

- Renovation in store for Luzon Building: Development of historic site to begin this spring; commercial and residential spaces planned (Tacoma Daily Index, January 13, 2005)

- Pacific Block closer to being sold (Tacoma Daily Index, January 14, 2003)

Todd Matthews is editor of the Tacoma Daily Index and recipient of an award for Outstanding Achievement in Media from the Washington State Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation for his work covering historic preservation in Tacoma and Pierce County. He has earned four awards from the Society of Professional Journalists, including third-place honors for his feature article about the University of Washington’s Innocence Project; first-place honors for his feature article about Seattle’s bike messengers; third-place honors for his feature interview with Prison Legal News founder Paul Wright; and second-place honors for his feature article about whistle-blowers in Washington State. His work has also appeared in All About Jazz, City Arts Tacoma, Earshot Jazz, Homeland Security Today, Jazz Steps, Journal of the San Juans, Lynnwood-Mountlake Terrace Enterprise, Prison Legal News, Rain Taxi, Real Change, Seattle Business Monthly, Seattle magazine, Tablet, Washington CEO, Washington Law & Politics, and Washington Free Press. He is a graduate of the University of Washington and holds a bachelor’s degree in communications. His journalism is collected online at wahmee.com.