Let us create …

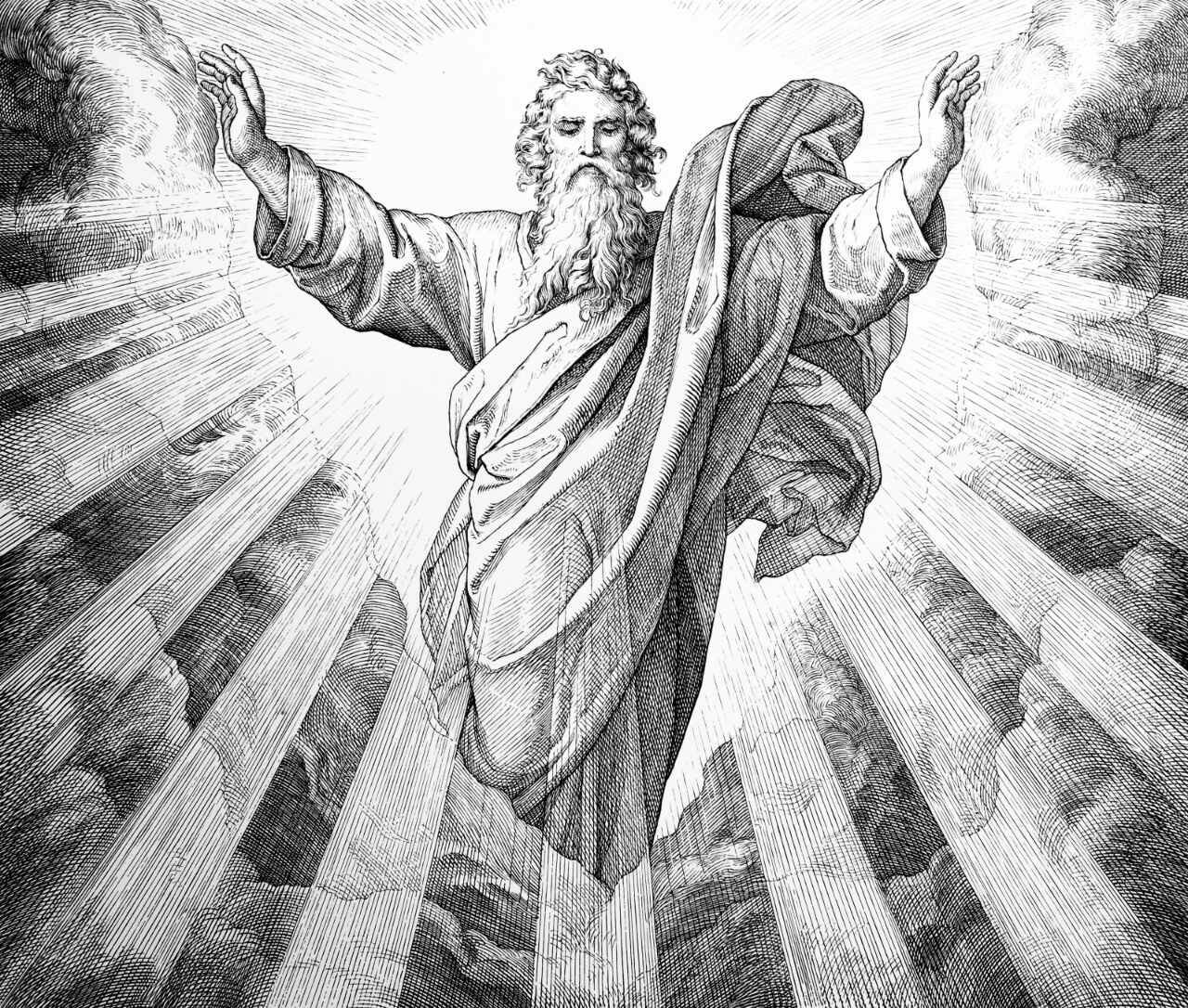

I’m going to use the Biblical creation story as my template in exploring the creative/entrepreneurial process, partly because about one third of humanity has grown up in the light (or shadow) of that story, and also because it’s the creation story I know best. And, since it has been held, adapted, interpreted, argued over and re-interpreted for millennia, it has proven, for better or worse, a reliable, or at least consistent, pattern for the creative process. Many readers see Genesis, especially the Creation story as a portrayal of a Creator.

I see it very differently; I see it as the ultimate story of creating.

In those short scenes, human being are portrayed with some simple (but as we see both in the story and our current set of challenges) but impossible purposes; to care for the garden, respect all of Creation and be leery of knowledge we are not prepared for.

In short, based on these historically influential accounts, we are creations created in the working image of a Creator. Creating is what we were literally created to do.

I know that many might reject using a story from the Bible because it is “too religious” — maybe it’s just me, but I am convinced that the Bible, beyond its sanitized verses taken vastly out of context, could be easily argued as the most anti-religious literary creation the world has ever known; after all, what is the Bible except a portrayal of “religious” bureaucrats and gatekeepers squelching, crushing, ostracizing, excluding and yes, crucifying any prophet or visionary who dared question the officially sanctioned orthodoxy?

Religious history (or human, or economic history) has barely changed since then.

What after all, is more frightening and unsettling than anything new?

And of course, what is more stultifying than what has been, seemingly endlessly, done before?

Such is human history in a nutshell; we fear change and innovation as much as we need it, and clamor for it.

It has been argued by some that we love novelty, but hate change. In other words, we can tolerate innovations slightly new, or tangible, visible improvements, but few things terrify most of us more than actual change.

Let us make …

I have heard it said that the Genesis story is one of creation by committee.

As many of us know from direct visceral, experience, committees don’t always have the best reputation for productivity — especially in new, challenging and innovative territory.

But it is also true that full and meaningful creation virtually never takes place in isolation. Every new development takes a full range of hands, eyes, perspectives, skills and (often conflicting) personalities and visions.

Creation labs, studios and centers, (even garages) are the stuff of history and urban legend.

But even then, concrete progress is slow, awkward and usually contentious and sometimes even frightening.

One of the ironies of creation is that the early process tends to be packed with negators, critics and “it can’t be done” voices.

And those voices are correct, at least for a while; any new thing is by definition impossible; until it happens.

And, as almost any student of history quickly learns, those negative voice eagerly claim credit for their contribution once the product proves successful.

And, as with the Genesis creation story, it takes an “us” to get things going.

From human flight to the light bulb to transistors, to artificial intelligence, it was all impossible, until it took shape in front of us and became, like “smart” phones, or household electricity, a necessity that we can barely survive without.

In short, “new” literally means something not seen or done before.

Nothing comes out of nothing

As Genesis tells us, nothing comes out of nothing.

As unspecified as it is, the “abyss” was in existence before

Let there be …

In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth. And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep.

— Genesis 1

The Genesis account starts with what could be called the ultimate raw materials — “without form and void” and, of course, darkness.

And then the famous “Let there be…” series of statements and creations.

“Let there be” could be better translated something like “I have an idea” or “What if we tried this…”

And then, if you know the story, a series of sequential “innovations” on the “formless void” take place.

Each one, building on or in response or reaction to what came before.

I don’t know about anyone else, but this is what my accumulative, recursive creative process looks like. Whether it is a writing project, a home improvement process or meal preparation, this “trying something, and then trying something else” process is, to my mind how any of us learns anything.

Few inventions come out as expected — or are used as intended

From gunpowder to AI to automobiles, the law of unintended consequences seems to prevail, even over the original intents.

And with some developments, like plastics, fossil fuels and nuclear weapons, the products and innovations take on an identity and power of their own.

In the Genesis account, free will is perhaps the ultimate foreshadowing of both the end of “paradise” and the beginning of human intervention in the larger world. With of course, repercussions for decision making, destiny and human reach and responsibility in the current, and future, world.

Even the best of creations don’t always end well

The Genesis story, of course, pivots at the point of expulsion from the garden, and, perhaps inevitably , leads the central characters to murder and exile within the family.

Any product or invention, not matter how promising, seems to hold this shadow presence.

How we respond to, or compensate for (or learn from) our own inventions (and their complications) is the foundation of much of our history.

Improvisation and accidental collisions and convergences are often more productive than intentional procedures

Invention, it could be argued, is often as reactive or serendipitous as it might have been intended.

The list of “essentials” accidently invented would be vast. You can see a profile of some of the most influential “accidents” here — bestlifeonline.com/accidental-inventions.

From penicillin to sticky notes to super glue, “accidents” have changed our daily and immediate lives (for the most part) for the better — or at least irreversibly.

And of course, from ChatGPT to cyber-currencies (and beyond) they will continue to do so.

It would be easy to make the argument that human history is still based on this formula of lurching forward, forgetting or neglecting our own most basic obligations, pursuing that Forbidden Fruit and experiencing exile and rejection.

Suffering or compensating for the consequences of our own actions and decisions is what constitutes our personal and social histories.

I don’t know about anyone else, but I’m ready for a new story line.