By Morf Morford

Tacoma Daily Index

It has become a cliché that we in America have never been more divided.

For whatever reason, we in our country have never been more eager to fight about everything from food to music to anything that gets our attention and, thanks to the internet, every one of us seems to declare ourselves instant experts on everything from toxicology to the Constitution.

From internet trolls, threats of war (or actual war) or labor shortages or extreme weather to ever-escalating economic uncertainty and of course, conflicts about realities and reactions regarding COVID have driven us all into a shared heightened level of arousal, if not anxiety.

In any area or level of conflict any one of us has (at least) two basic choices; we can escalate or de-escalate the situation.

In virtually any situation from neighborhood or family conflict to global nuclear conflict, the wisest and most prudent response is to de-escalate.

Escalation, as every pre-school teacher, or mother, knows all too well, will only make the situation worse.

Every family, every business and certainly every nation functions better, even thrives, the stronger its shared vision and sense of identity.

As our Founding Fathers put it, “United we stand” followed by “Divided we fall”.

Every set of us, from family to rock band, will proceed only as far as our unity will take us.

We have laws, rules and expectations, some formal and officially encoded, while others more unofficial, even unspoken (and certainly unwritten) define and frame who “we” are and who those who threaten us might be.

To say that we in the United States have a conflicted understanding of where (or what) those parameters might be would be the ultimate understatement.

The nation we consider ourselves closest to, and took our language from, and consider our closest ally in most ways, we have in fact been at war with – twice.

Laws, obligations, rights and responsibilities should lie equally distributed across a shared national landscape.

Any nation, especially one that literally calls itself the United States, cannot sustain its identity if an act or substance, or basic right (like marriage) or medical procedure is legal in one state, but not in a neighboring state.

A modest proposal

Our laws – and how make and enforce them – have been points of contention for decades – if not all of our history.

Who is, or is not, or should never be, a citizen?

Are immigrants and political refugees welcome? Or not?

Do we offer, and respect freedom of religion? Or do we reserve the right to privilege some and denigrate others?

In other words, do we believe what we say we believe?

Or do we believe in some unspoken, unwritten yet somehow shared (by some at least) set of rules that are somehow more binding and universal than our written laws?

I have a suggestion for a simple guiding principle for more enduring, fair and just laws; laws should be proposed, written, and if practical, primarily enforced by those most directly impacted by those laws.

We have a long history, for example, on local and national levels, on every issue from zoning to business to marriage or voting rights, of older white men making laws that apply to everyone except themselves.

What if, for example, laws regarding women, from assault to pay to birth control, were made predominantly, if not exclusively by, women?

What if laws, or policies or funding for schools were made by those directly affected? By local parents, teachers and even students?

Or what if laws and policies regarding homelessness were not made by those with secure housing, but those who know, or at least have known, housing insecurity?

Or what if laws regarding drug use were made by those who know all too well the hazards of drug use – and the difficulties of finding effective treatment programs?

Drug laws, after all, have little, if any effect on the amount of drug use in any given society.

Those who choose to use drugs will use them no matter what the law says, and those who do not use them will not change our behavior if laws change.

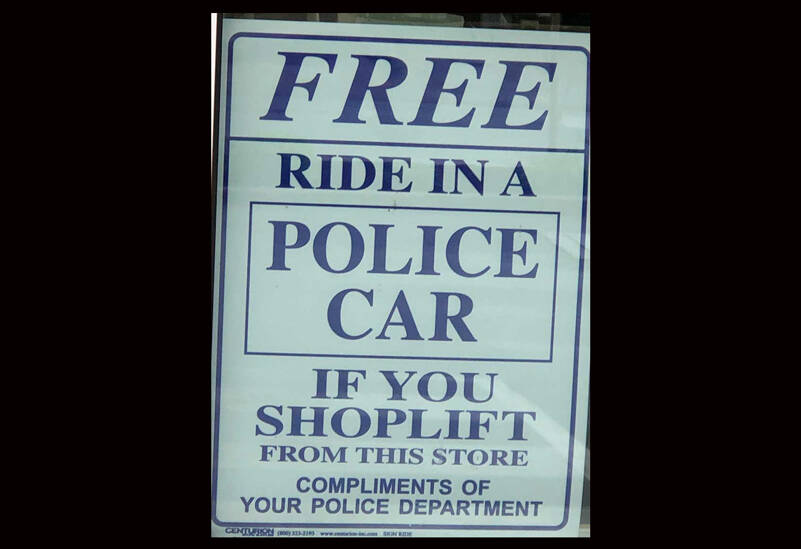

From speed limits to drug laws, it seems that we have forgotten a simple but unrelenting guiding principle – the purpose of laws.

The purpose of laws

Only a virtuous people are capable of freedom. As nations become corrupt and vicious, they have more need of masters. – Benjamin Franklin

Any given law has a specific application – but virtually every law shares a common set of assumptions.

Every law should contribute to a sense of well-being and safety – even trust – among those who live under – and enforce it.

Unfair laws dissolve trust – and no one, those who live under – or enforce them are safe or protected by them.

Some individuals, and apparently some regions, seem to require stricter laws, others have something like a membrane of trust that binds and supersedes written laws.

Some of us, to a large degree, do not need laws.

When it comes to driving for example, I rarely take note of the posted speed limit. I drive along with everyone else, and according to the conditions. In over 50 years of driving, I have never received a citation for any driving infraction. My guiding principle is to drive safely – for myself and any others around me.

Isn’t that the purpose of every law? To ensure safety and promote civic responsibility to all of us?

From building codes to business regulations to food safety, isn’t the health and well-being of all the primary concern of the law?

Laws should never be onerous or vindictive – they should in fact, guarantee and protect our freedom.

And any law or rule should have one over-riding goal – to make us better people – better citizens and better neighbors. And more, not less, trusting of each other.

Laws and rules, in far too many cases have become unyielding and abstract. And, all too often, become the opposite of what good laws should be.

Laws are not, at root, about following rules, they are the foundation of a solid and responsible set of citizens who respect those who make and enforce our laws. But that respect is not automatic – it is earned and deserved.

As the Chinese philosopher Zhuangzi put it, “Rewards and punishments are the lowest form of education”.

Laws and rules should, at their best, stir us all to clean up after ourselves, take care of our communities and, encourage us to be better people.

Laws, again, at their best, should be borne lightly and should, in most cases, be more about freedom than control. There should be very few of them, and in most cases, we should barely notice them.