By Morf Morford

Tacoma Daily Index

‘What do women want?” Sigmund Freud famously asked. A little over hundred years later, as our economy makes hesitant steps toward recovery, a more comprehensive question might be “What do any of us really want?”

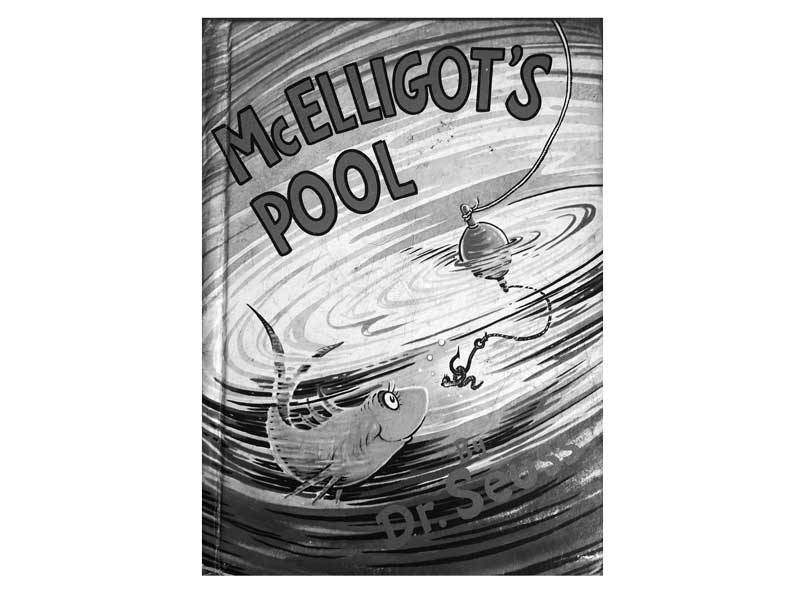

In a market where a Dr. Seuss children’s book goes for several hundred dollars, for no particular reason, since literally hundreds of thousands were published and no one in a reasonable world would ever “need” one, or where a pair of shoes could cost as much a car, or a car (like a Bugatti or Lamborghini, could cost as much a small (or not-so-small) business or even the budget of a small city, with some models costing up to four million dollars.

It becomes obvious that when we are talking about cars, we are talking about far more than reliable, safe and comfortable transportation.

When we pay a higher than standard price (based on cost of production, mark-up and a few other basic principles of business) we are looking beyond (maybe even far beyond) standard market forces and motivations for buying. We might say that we want quality, durability, design, or preferred customer service, but I think, perhaps like acknowledging racism, we rarely see what is plainly in front of us.

When Steve Jobs was first promoting the iPhone, back in 2007, cell phones already existed, laptop computers were common (and affordable) and virtually every application or program on the iPhone was available somewhere else, why would anyone “need” a smart phone?

As he went on to admit, when people, and potential customers don’t know what they “need” or even “want”, the true entrepreneur needs to tell them.

Here’s the quote in its entirety;

“Some people say give the customers what they want, but that’s not my approach. Our job is to figure out what they’re going to want before they do. I think Henry Ford once said, ‘If I’d ask customers what they wanted, they would’ve told me a faster horse.’ People don’t know what they want until you show it to them. That’s why I never rely on market research. Our task is to read things that are not yet on the page.”

As planners, business owners or entrepreneurs, maybe even as community members or parents, we need to continually be the ones who “read things that are not yet on the page.”

Like frustrated toddlers, most customers, for virtually any product, from vitamins to SUVs, are driven, influenced by, even distracted by, needs and wants that we can barely define, let alone distinguish.

Among other things, many of us buy (or fantasize about buying) ultra-expensive items because we are looking for, not shoes or transportation, but validation.

Have you noticed the size of trucks on American streets lately?

In an era of near-tangible anxiety and certainty, with increased and record-setting numbers of homelessness, unemployment and evictions, we Americans take refuge where we have always taken refuge – in our vehicles.

We want safety, stability and an abiding sense of control. And our vehicles give it to us. We might not find it anywhere else, but at the wheel of our (McMonster) truck, we can find what we most want, need and can’t put into words.

You’d think that we human beings would pay the most for those things that we need, or even want the most.

Marketers know better – like dogs fighting over a single toy, most of us want what we want, not because we actually want it, but because someone else wants it.

If you think about our economy in historical terms, most of the basics, from food to clothing are vastly more accessible and affordable to the vast majority of us than any other time in history. These basics take a smaller and smaller percentage of our daily budgets with each passing paycheck.

Housing, of course, is the wildcard in this free-form inverted economy.

I wish the solution to housing was a simple as many politicians say; they say “we need more housing!” as if supply were a factor in our long obsolete supply and demand economy.

If we needed “more housing” we would not have nearly as many empty units as homeless people. And many areas have many more abandoned properties and housing units than people who might occupy them.

The underlying principle of the McMonster truck might help explain what seems like an astounding mis-match of housing need and housing cost.

Housing, like transportation, is a basic need in our (or any society). Shelter, possibly more than anything else, even more than food perhaps, should be affordable and accessible to all.

Homeless children and families should be an affront to us all. No civilized culture should ever excuse such a development. It has taken decades for our homelessness crisis to take root, not only in our cities, but in our consciousness and identity.

As much as we might decry it, even deny it, homelessness on a massive scale, across every age has become, however we may sugarcoat it, a near permanent blight on our urban (and even not-so-urban) landscapes. But like McMonster trucks, which are not primarily about transportation (or even the traditional “work” aspects of a basic truck) the housing that most areas are constructing have little to do with “housing” in the usual sense.

Luxury apartments are not a “solution” to homelessness – in fact in many ways, becoming increasingly obvious, high-end housing raises prices and makes more and more housing more (literally) exclusive (as in excluding) to more and more people in greater and greater need.

Some housing advocates use the term “houseless” in place of “homelessness”. The word “homeless” has a semi-permanent, if not moral, tone to it. But being in need of shelter is not an abstraction and is rarely permanent and certainly not necessarily a “moral” or ethical condition – or even the result of “bad” choices.

Being homeless just means not having safe and reliable shelter. This could be one night or a thousand, urban, suburban or rural. And this could impact any age, occupation, education or ethnicity.

Do we, homeless or housed, get the housing we “want”?

Knowing human nature, I’d have to say that we almost never do.

But again, the principle comes back to knowing what we want.

Do we, as individuals or as neighborhoods, want more high-end housing?

Housing, as you may have noticed, is being marketed, not as a solution to homelessness or even housing affordability, but as a commodity being sold on a scarcity model.

Instead of building solid housing that could be used for generations for a stable, if not ever expanding market, most housing that I see seems to be quasi-temporary (built for a few decades) and geared to a market least in need of housing.

These housing projects are almost always framed in the traditional constructs of luxury; a sense of emergency and the implied,if not explicit, condition of exclusivity.

Somehow we have come to believe that housing is different from every other item that we buy, sell or use.

It isn’t.

What do “homeless” people want?

They want what any of us want; a place to call their own, a place to call home. They don’t need a program or to be rescued.

Like each one of us, homeless people want the results of shelter (security, safety, something to call their own) providing that, not fancy counter-tops or tax-abatements is what will permanently take care of the homeless “problem”.

What “women want” and what homeless people want and need, is to be listened to.