The Senate Law and Justice Committee held a hearing Feb. 2 for legislation that would make it easier to commit someone to involuntary mental health treatment.

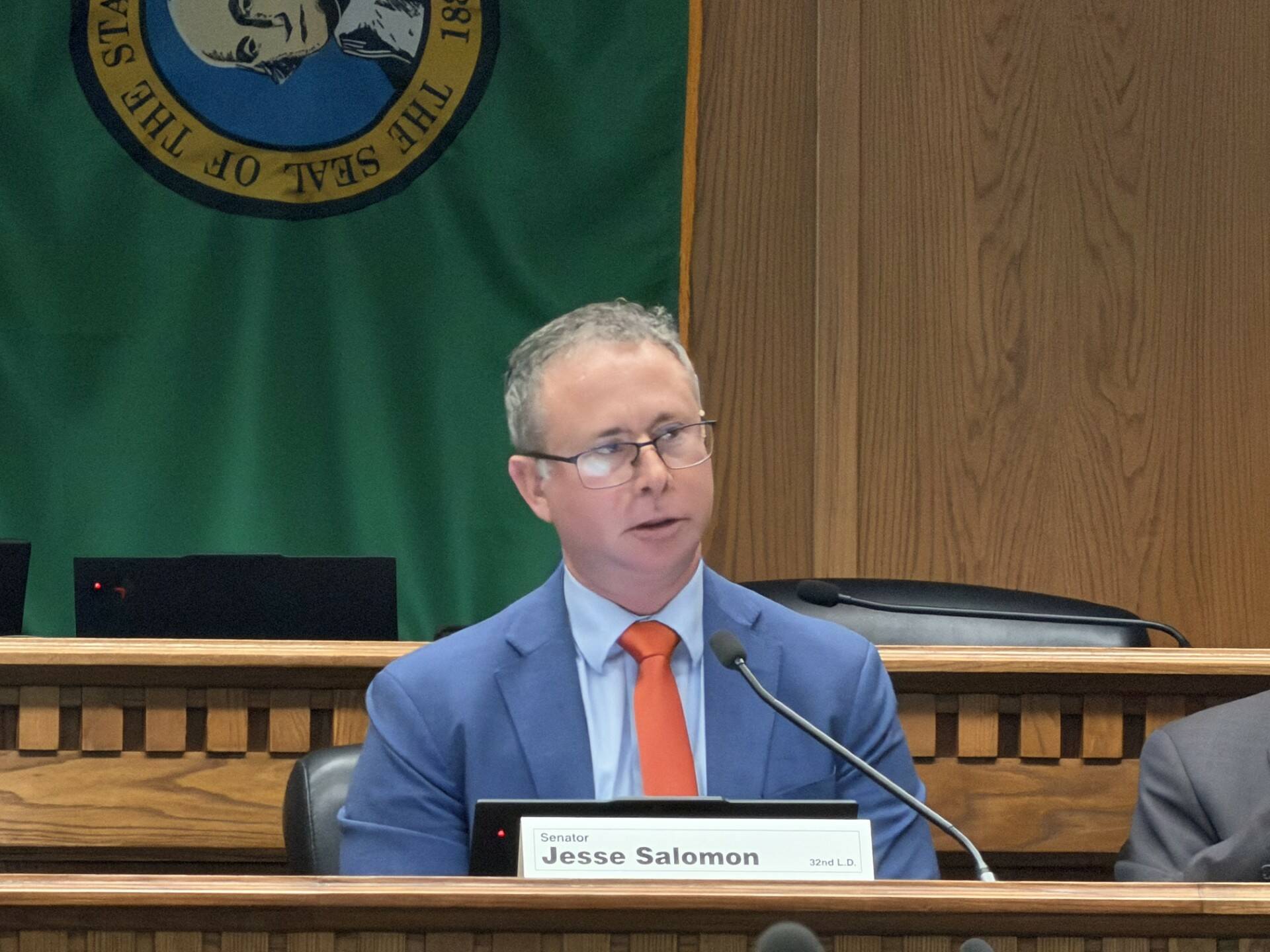

Sen. Jesse Salomon, D-Shoreline, is the prime sponsor of Senate Bill 6296, which is scheduled for an executive session Feb. 3.

Salomon said there is a need to change Washington’s Involuntary Treatment Act.

“We heard from a designated crisis responder, or DCR, who asked, ‘Do you want to know where the list is of persons we tried to detain for involuntary treatment, but could not?’” he said. “‘It’s the jail roster. Our jail is full of individuals we tried to detain and could not, and then they committed a crime.’”

SB 6296 would, in part, streamline the process of admitting someone to assisted outpatient treatment (AOT), an involuntary mental health treatment program for adults with severe mental illnesses or substance abuse disorders. AOT is a type of less restrictive alternative treatment to detention.

Specifically, the policy would no longer require a declaration from a clinician who has examined the patient to accompany a petition for AOT.

Robert McCullough, a licensed mental health counselor and AOT therapist in Snohomish County, expressed support for removing the declaration requirement in order to keep people off the streets and prevent them from re-offending.

The measure would also expand the list of people who may petition for a person’s detention if a DCR, a clinician trained to respond to behavioral health crises, decides not to detain them.

Under Joel’s Law, the list of potential petitioners include someone’s immediate family member, guardian or tribe. Joel’s Law was named after Joel Reuter, who was killed in a standoff with Seattle police while suffering from a mental health crisis in 2013.

SB 6296 would add to the list any family or household members, intimate partners, the person’s conservator, a representative of a human services provider that has served the person and other specified medical, behavioral health, and human services professionals.

Joel Reuter’s father, Doug, spoke in support of the proposed expansion.

“It helps get people treatment [who] really need treatment,” he said, “and I would encourage anything that can be done legislatively to strengthen Joel’s Law rather than weaken it.”

However, Laura Cissna of the Washington Association of Designated Crisis Responders said the petitioner expansion increases the risk of misuse by “allowing abusive ex-partners to initiate involuntary commitment against protected individuals.”

Another aspect of the bill that raised concerns for some was the requirement for law enforcement to assist DCR during the detention of a person.

James McMahan, the policy director of the Washington Association of Sheriffs and Police Chiefs, cited the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeal’s ruling in Scott v. Smith as a potential obstacle.

In the case, the court found that two Las Vegas law enforcement officers were not entitled to qualified immunity when they used force to detain a man experiencing a behavioral health crisis who died during the encounter.

“I want our officers to respond to these and… help people who need help,” McMahan said. “But we can’t intentionally or unintentionally drive our officers into a cliff where they have to do the thing that they’re now subject to immense liability for.”

The Washington State Journal is a nonprofit news website operated by the WNPA Foundation. To learn more, go to wastatejournal.org.