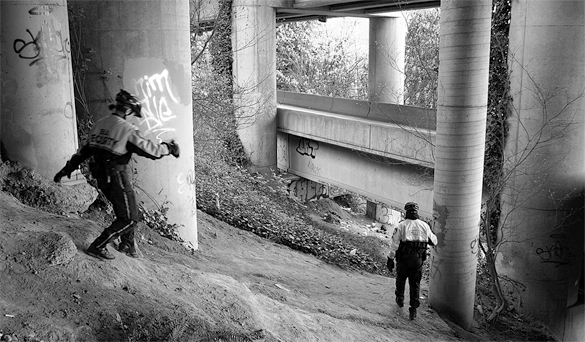

THURSDAY MORNING BENEATH Interstate 705 in downtown Tacoma, and Business Improvement Area (BIA) bike patrol officers John Leitheiser and Sarah Kirkman scramble along a hillside. The officers are dwarfed by scores of graffiti-tagged colonnades, and scale a massive hillside that stretches toward Foss Waterway like the open face of a wave. As they step over trash, old sleeping bags, human feces, broken lawn chairs, and dirty needles covered with loose dirt, it’s not long before Leitheiser and Kirkman come across an encampment. A man and a woman slumber beneath layers of blankets and sleeping bags. On a dirt ledge beside the pair, Leitheiser points to drug paraphernalia: a pipe with chalky residue, a bent and scorched tablespoon, and a lighter.

“Rise and shine,” says Leitheiser. It’s a voice so friendly and calm, you would think he were delivering room service. Leitheiser’s thick build and coarse, slightly twanged tone belie a friendlier side: he has been known to move through encampments singing a theme song from a bygone Raisin Bran commercial — an effort to assuage any tension he might encounter from the people he moves out of downtown doorways, parks, and I-705 overpasses. “Good morning,” he continues. “How are you doing?” After a pause, he adds, “You’re trespassing.”

An African-American woman pulls layers of covers away from her face and squints at the officers. She’s groggy and tired. “I didn’t see any signs,” she says. “Is it trespassing down here?”

“Yeah, it is,” replies Leitheiser. “We’re going to give you a few minutes to get your things and move out.” He asks if she’s tried some of the local missions or homeless shelters. The woman, who identifies herself as Chavella, 50, says she has, but they’re always full before she can get in. Moments later, her companion — a man wearing a hooded sweatshirt pulled tight over his head — stirs. He sits up and stares at the hillside below. He doesn’t speak to Leitheiser or Kirkman, nor is he confrontational.

It took a lot for Chavella and her companion to make it down here. They had to walk along the white stripe of an on-ramp dipping down to Schuster Parkway, climb through a chain-link fence accessible by way of a broken lock, and scurry down the hillside.

While the pair collect their belongings, the two officers convene back on street level, in a parking lot near the old Northern Pacific building. Though a chain-link fence was installed to discourage hillside access, Leitheiser and Kirkman say homeless people find ways to gain access.

“They are so desperate that it doesn’t stop them,” explains Kirkman, 25, with a tone of compassion.

Moments later, Chavella and her companion emerge. They clutch blankets and sleeping bags, and shuffle up the on-ramp. Leitheiser offers a list with contact information for shelters in Tacoma, but the pair refuse it. Before long, they disappear around a corner, presumably in search of another place to camp.

It’s a common scene for Leitheiser and Kirkman, two of 10 patrol officers assigned to the BIA — an 84-block section of Tacoma that stretches north to south from South Seventh to South 21st Streets, and east to west from Cliff Street to Court D. The officers are employed by Pierce County Security, which has a contract with the BIA to implement the security program. Property owners pay for the service, $311,000 annually, through an assessment on square footage.

Though they aren’t law enforcement officers, BIA security officers provide a key resource for the Tacoma Police Department, defusing many nuisance situations — sleeping in parks and public places (231 incidents in 2006, according to BIA statistics), drinking in public (145 incidents), and property damage (211 incidents) — before they tap police resources.

Though BIA officers lack authority to arrest people, nor carry firearms, they do provide a wealth of surveillance information on alleged drug dealers and illicit activity downtown. When a TPD car rolls through a troubled intersection, it typically clears the area. A BIA patrol officer on a bike, however, is a little craftier and more clandestine. And a drug dealer who knows BIA officers can’t make an arrest might continue their activities, allowing officers to gather information that can be passed along to Tacoma police.

“We’re involved with them quite a bit,” says Tacoma police officer Jim Pincham, who is one of two TPD officers also assigned to the BIA. “People are more apt to do stuff like that if they see bike patrol officers, rather than if they see Tacoma police officers.”

ON TREK MOUNTAIN bikes, working out of a small office near Commerce Street and South 11th Street, officers respond to a variety of issues. During a two-day period last week — four hours on Thursday, and an overnight shift from 8:00 p.m. Friday to 3:00 a.m. Saturday — this reporter followed bike patrol officers as they encountered reports unusual (a dead cat near the Spanish Steps; a low-income-apartment resident throwing trash onto an alley and firing a toy gun at nearby City utility workers) and mundane (a woman who lost her driver’s license downtown — the license was recovered on a sidewalk and returned to the owner).

Officers also made a steady round of patrols to known “hot spots”: the corner of South Ninth Street and Commerce Street, where loitering and alleged drug dealing are rampant (according to TPD statistics, the corner regularly tops a list of most calls for emergency services, and it’s frequently the scene of so-called “SET” missions aimed to arrest drug dealers); Fireman’s Park, where a gazebo’s wood benches and half-walls are perfect cover camping, loitering, and drug use; the abandoned Elk’s building, where transients managed to cut a fence and break a window to gain access inside; and even more visits beneath I-705 underpasses to monitor homeless encampments.

“Once you’re down here for awhile, the biggest part of the job is learning the area,” says officer Johnny Perry. “You learn every inch of where people hide, where people do their drugs, where all the illegal activity takes place. Once you get that part of it down, when you ride by on patrol, you’re automatically checking all these places. It becomes second nature after you do it for so long.”

One hub of activity: Fireman’s Park.

On Friday night, officers visit the park three times to remove a total of seven people asleep in the park’s gazebo. During the first visit, around 9:00 p.m., Leitheiser discovers a 65-year-old man, dressed in soiled blue jeans and a dirty parka, asleep beneath the gazebo’s bench. As he grabs his blanket and prepares to leave the park, Leitheiser offers a list with the names and addresses of local missions. The man is familiar with all of them, but wants to go it alone. Later on, during a patrol up the hill along Court D, Leitheiser discovers the same man asleep under a tree. Again, the man is polite; again, Leitheiser moves him along.

The second visit to the park, around 10:00 p.m., reveals five men sleeping in the gazebo. Three men quickly pack their blankets and leave. Two others put up a brief protest. As Leitheiser and his officers discuss park rules with the two men, officer Perry circles the gazebo with a small flashlight, pointing out some of the evidence of trouble.

“There are clues to tell you people were here,” he explains. “You look for empty plastic sacks with marijuana residue, blunt wraps, syringe caps, and trash.” He edges around the gazebo a few moments before he comes upon a Pepsi can, partially crushed and modified with pin-point holes for smoking marijuana. “Sometime today,” he adds, “somebody came down here, made this, and smoked marijuana.”

A few steps away, more loot: a syringe cap, a glass pipe blackened at both ends and used to smoke crack cocaine, and the concave base of a candle holder scarred with the brown residue of cooked narcotics. “If you find a lot candles sitting out, that’s a sign, too,” officer Perry explains. “People take the tin off the bottom of the candles, fill them up with water, and use the candles to cook their drugs.”

Ten minutes later, Leitheiser is back on his bike. Two officers on regular patrol discover a man sleeping beneath I-705, near the Tacoma Art Museum. Leitheiser cruises through an alley west of Pacific Avenue, between the Washington Building, post office, and Heritage Bank tower. When he arrives, it seems like the perfect spot to disappear for some sleep. It’s invisible to an average passerby. But for BIA patrol officers, it’s a spot frequently checked.

“He’s probably going to head south,” explains one female officer who asked not to be identified for the story. “He’s basically looking for shelter or somewhere to sleep where they’re not disturbed. Usually, if people know we’re out patrolling, they at least leave the BIA boundary.” If he heads south, she explains, he might find refuge in a wooded area where I-705 and Interstate 5 connect, or an open field near South Tacoma Way. Though officers list the names of nearby missions, the man dismisses them.

Though officers are charged with safety in the BIA, I ask Leitheiser why they move homeless people out at a time of night when businesses are closed and streets empty.

The reasons are twofold: if officers can encourage someone out from under a freeway overpass an into a shelter, it’s a good resolution; also if areas aren’t regularly patrolled, word quickly spreads. “The next thing you know, you have tent cities popping up in certain areas,” he says.

LEITHEISER, 54, STARTED on BIA patrol when the program was created in 1994. He is the most senior member on the security patrol. He supervises every officer, trains every new-hire.

“I’ve got nicknames down here,” he explains. “They call me sarge, pops — these people on the streets know who I am.” Indeed, it’s the first thing you observe following him around downtown. As he cruises along sidewalks, downtown residents and shop owners stop him to chat, share their concerns, and learn what’s new.

Leitheiser was hired as an officer after working 20 years as a pipefitter. A back injury forced him out of the industry. When he started at the BIA, officers patrolled on foot. Bikes were introduced two years later, and it was a welcome addition: easier and more efficient for Leitheiser and his colleagues to patrol the area.

“People would give you a bad time because they knew you couldn’t catch them,” he says. “Now we’re right on top of them. It made a big difference.”

Downtown for 13 years, Leitheiser has seen alot.His most strange and memorable story occurred seven years ago. A man climbed up to the old station house on the 11th Street Bridge, stepped out on a platform, and prepared to commit suicide by jumping. Instead, he found a dead body on the platform.

“He climbs all the way down the 11th Street Bridge, comes up to the office, and tells me about,” Leitheiser recalls. Officers were dispatched to the scene, where they, too, discovered the corpse. “A guy down there, stiff as a board, scared this guy from jumping,” Leitheiser says, shaking his head.

Patrolling downtown Tacoma in the mid- to late-1990s was dangerous. Whereas today the corner of South Ninth Street and Commerce Street is downtown’s hotspot, the corner of South 15th Street and Pacific Avenue — an area lined with shelters and seedy bars — was a crime magnet.

“Within a three-block radius there was somebody shooting up, sexual acts, you know, it was just out of hand,” Leitheiser explains. “People would hide inside [bus stops] and have their sex acts right there. Or they would shoot up drugs. It was just a constant thing.”

And whereas today BIA officers might receive three calls in one eight-hour shift, back then it was common for BIA officers to receive five calls on single blocks in pockets of the city, at any hour of the day.

It was in the mid-1990s that BIA really started to forge a relationship with TPD. Because BIA officers exclusively patrolled downtown, they could gather information to identify alleged drug dealers. That information would be used during TPD SET missions aimed to make arrests. It’s a tactic that exists today.

Late last year, when property owners near the corner of South Seventh Street and Broadway complained of property damage due to chronic graffiti, BIA officers collaborated with TPD. Leitheiser and his team were allowed after-hours access to nearby businesses, where they hid out for two weeks conducting surveillance. That information was then passed along to TPD. On Jan. 1, TPD and BIA teamed to apprehend and arrest five people spraying graffiti on area buildings.

When Leitheiser pedals downtown streets today, he sees progress. The illicit activities that he saw throughout the city are mostly gone. The areas that do pose problems are well-known and regularly patrolled.

“I’ve never had an officer injured, and that’s because we treat these people right,” he says. “These officers are unarmed. I’ve got women patrolling down here. A lot of these people on the street aren’t bad people. Respect, both ways, goes a long way.”

AROUND MIDNIGHT, OFFICERS return to the gazebo in Fireman’s Park. A homeless man camped out refuses to leave. It’s the first time this evening officers encounter someone who is combatant. Leitheiser offers a cigarette (“it’s my version of a peace pipe,” he explains), which the man accepts.

The fidgety man has stringy blonde hair, and wears a puffy parka, blue jeans, and tennis shoes unlaced. Three garbage bags filled with his belongings sit next to him. He is familiar to officers — reportedly kicked out of several missions and shelters for fighting. Though he doesn’t threaten BIA officers, he refuses to leave. As a rule, BIA officers try to defuse and resolve non-threatening situations before they reach TPD. Most instances are resolved without any conflict. However, some close calls exist. Officer Perry recalls a time last winter when a man who refused to leave Fireman’s Park flashed a buck knife and charged an officer.

“You got to be aware of your surroundings, aware of your situation, always thinking,” says officer Perry. “That’s how you keep yourself out of trouble. If it gets too dangerous, you get out. If someone pulls a gun, you go. It’s something you have to keep in your head when you do this type of job.”

On this night, Leitheiser calls TPD. Two patrol cars roll up 10 minutes later (one with a K-9 officer, who aggressively sniffs his way through the park’s berms and grassy areas), but the man left a few minutes ago.

Two hours later, bars and restaurants near South Ninth Street and Pacific Avenue empty.

It’s a bizarre scene.

Earlier, an intoxicated woman leaving a pub fell off a sidewalk and landed face-first on the pavement. Officers rode over to make sure she was OK. The woman, embarrassed, was escorted to her car by two friends who appeared sober and prepared to drive her home.

An argument between two women in two large groups spilled out of a bar and onto the sidewalk. Officers rode up to the scene, conflict defused.

A man smoking a cigarette asked officers if they saw a brown Saturn parked nearby. The man’s girlfriend took a cab home, and sent him downtown to pick up her car. Leitheiser suggests he check an alley behind a nearby restaurant. Five minutes later, the man pulls up, rolls down his window to thank Leitheiser, and drives away.

Presently, two BIA patrol officers set up outside an after-hours club. As they chat with patrons, Leitheiser points out a few things: a short, stocky woman wearing a black ball cap over a long pony tail is dealing drugs to a man in a nearby doorway. Leitheiser says she’s a familiar presence here. Her hands move quickly, but it’s all there, he says: a plastic pouch filled with white powder, a flash of cash, and a quick exchange.

BIA officers don’t have the authority to arrest anyone. But they do have the ability to collect information and pass it along to TPD. On this night, one BIA officer notes the presence of a new car typically associated with the alleged drug dealer’s accomplice, who is sitting behind the wheel. By 3:00 a.m., officers have gathered enough information to pass along to Tacoma police officer Pincham Monday morning.

Todd Matthews is editor of the Tacoma Daily Index and recipient of an award for Outstanding Achievement in Media from the Washington State Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation for his work covering historic preservation in Tacoma and Pierce County. His work has also appeared in All About Jazz, City Arts Tacoma, Earshot Jazz, Homeland Security Today, Jazz Steps, Journal of the San Juans, LynnwoodMountlake Terrace Enterprise, Prison Legal News, Rain Taxi, Real Change, Seattle Business Monthly, Seattle magazine, Tablet, Washington CEO, Washington Law & Politics, and Washington Free Press. He is a graduate of the University of Washington and holds a bachelor’s degree in communications. His journalism is collected online at wahmee.com.