Feeling zoned yet?

By Morf Morford

Tacoma Daily Index

If you want to see a room full of people as their eyes glaze over all at once, just talk about zoning.

It is not an etymological accident that we might describe someone in a disconnected, zombie state as being “zoned out”.

Love or hate the urban design usage of the word “zoning”, it is an idea that, whether we recognize it or not, impacts us all – and, especially when it comes to our own neighborhoods, we care about it passionately.

The premise of zoning is very simple; categories of development and construction should be controlled, and most of the time, kept in similar areas.

Most of the time, this system works. Most of us like it – most of the time.

It seems reasonable; keep single-family homes in this neighborhood, businesses in that cluster and industrial sites over there.

As I mentioned above, most of the time it works – until it doesn’t.

And most of us like it – until we don’t.

Zoning is the ultimate example of “one-size doesn’t-fit-all”.

What works in one neighborhood might be a disaster two blocks away. And one zoning principle might be an answer to a problem that existed a decade ago and might, because of demographic changes or shifting technologies, be irrelevant or even destructive to a neighborhood.

Buildings and streets are expensive to build – and sometimes even more expensive to remove or remediate.

Should historic buildings be demolished? Restored? Redesigned and modernized?

It all depends on the constantly shifting moods, needs and preferences of the community.

The urban design catastrophes of previous generations might appall us now, and we might have to ameliorate (and live with) their choices for generations, but they (presumably) had good intentions and thought they were making the best and most appropriate decisions – maybe even on our behalf.

I love human variability. And nothing emphasizes human variability like the near constant attempts to control, commodify and categorize the inherently uncontrollable by insisting on ideological purity, political correctness, systematic theology or architectural consistency on an unwilling participant.

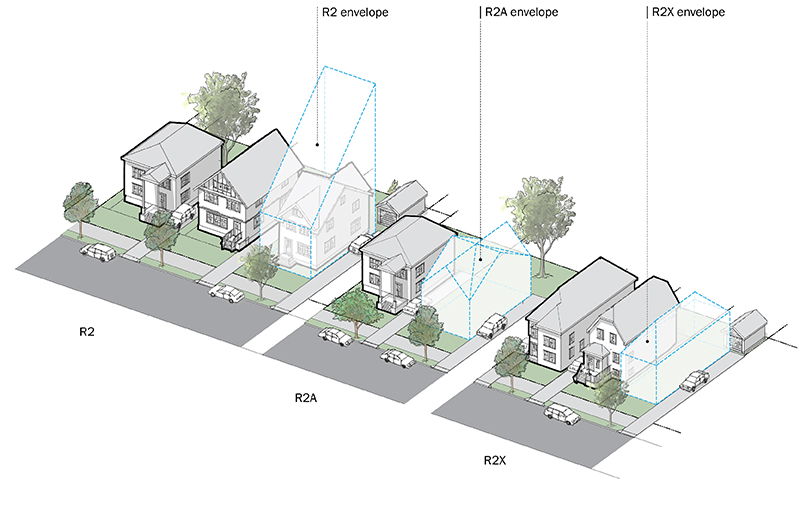

I understand the appeal of uniform zoning. Consistency of style and size (especially height) or thematic design is attractive and can define a neighborhood or community.

Zoning should facilitate productive and appealing construction. In other words, zoning should not be noticeable, but it should be a barely visible guiding force that allow a community to define and express itself.

Virtually all of the historic (and appealing) neighborhoods of Europe, for example, have what we might call “mixed use” zoning – which looks very little like the American version.

Mixed use, at its best creates an urban environment active at all hours, making optimum use of infrastructure. Smaller households can have a greater range of options (rather than just detached homes).

Mixing housing types could increase housing affordability and equity by reducing the price point that exclusive, segregated areas experience.

By providing housing near commercial and civic activities, planners could reduce the dependence of the elderly and children on cars.

Enabling people to live where they can shop, work, or play could reduce car ownership and vehicle trips, increase pedestrian and transit use, and thus alleviate the environmental and social consequences associated with automobile use – like parking and traffic.

Instead of vital, active urban centers, our zoning tends to produce vistas of antiseptic, look-alike housing clusters. Whether it is cul-de-sac centered suburbs or endless apartment blocks, the effect is the same; a mind- numbing sterile conformity that defies any attempts at creating a sense of welcome, belonging or community.

In any of these settings, how often to you see residents – or visitors – linger as they would in a more conducive social setting?

One of my favorite things to do when I am in a city for the first time, is walk around. I like to get a human-scaled, slow-paced view of a city or neighborhood.

With the eye of an outsider it becomes immediately obvious which neighborhoods are welcoming – and which are not.

The irony, especially in older areas, is how few were designed to be that way.

Few neighborhoods (I presume) were designed to be inhospitable – but based on the prevalence of jagged barricades, sterile blank walls, lack of safe sidewalks or any amenities for pedestrians, consideration for humans seems to have never been in the plans.

Developers tend to complain about “accessibility” guidelines, like sidewalk ramps, but the reality is that accessibility works for far more than any who might be designated as “disabled”.

If you want a neighborhood that will appeal to families, you better have ramps for baby strollers, scooters and all kinds of pedestrian powered vehicles and carts.

Picture a traditional European village of a few centuries ago; an established family would have a home with a shop, or workspace (or even animals) on the bottom and a residence above. This is the ultimate “mixed use”.

This solves multiple urban problems at once – no commuting, no parking problems, and the “traffic” is most likely to be pedestrians – meaning potential customers.

A few years ago I took a solo bike ride through a neighborhood in South China (outside of Zhejiang, a small town about triple the population of Seattle). It was after dinner in what appeared to be a suburban area of single-family homes.

It was a hot humid evening and almost every home had a street-facing garage – with doors open.

As I quietly rode my bike past I was stunned to see that virtually every garage held a small-scale factory or assembly line – some with a string of perhaps eight automated sewing machines, some with rows of tables of fabric, food or electronic devices.

In short, it was an entrepreneurial hive cleverly disguised as a residential neighborhood.

I mention these two scenes because they are the ultimate enduring historic expression of mixed use – with a focus on local production, skills, identity and customer service – yet they would be illegal in almost any city in America.

My argument is very simple; zoning should make our neighborhoods more interesting, appealing and productive. Is that so difficult?