Forty years ago, a Tacoma resident named Ellida Lathrop traveled the country while working as a consultant for the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA). As she visited different cities, Lathrop noticed all of the public art on display in city parks and on downtown street corners. Closer to home, she watched as Seattle built its public art collection, too, and wanted to see the same thing happen in Tacoma.

What became clear to Lathrop was that many of these cities were creating public art by enacting an ordinance known commonly as One Percent for Art. The law was exactly what it sounded like—one percent of the budget to construct public buildings would be set aside for public art. Lathrop, who was also president of the Tacoma-Pierce County Civic Arts Commission, led a campaign to enact the One Percent For Art ordinance in Tacoma. In the end, Tacoma City Council unanimously enacted the ordinance in 1975.

Although the law was on the books, a terrible economy meant very few public buildings were constructed—a fire station here, a branch library there—and for many years the ordinance didn’t direct much money toward public art.

Five words—A Dome of Our Own—changed all of that.

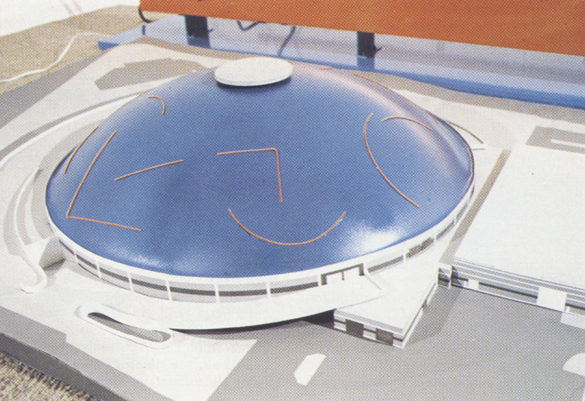

In the late 1970s, support was growing to build a mini-dome near downtown Tacoma. In March 1980, Tacoma voters approved a plan to spend $28 million to build the indoor area. The One Percent for Art ordinance meant $280,000 would be set aside for public art. While the building was under construction, the City of Tacoma convened a panel of art experts to attract high-profile artists and their proposals. In the end, four artists submitted plans—Stephen Antonakos, Richard Haas, George Segal, and Andy Warhol. Antonakos envisioned a roof painted blue and illuminated by neon arcs and angles. Haas imagined a cluster of stars and constellations. Warhol saw the Dome draped in a bright flower. Segal’s proposal, destined for the inside of the Dome, included statues of trapeze artists and acrobats. In the end, Antonakos’s neon design was briefly selected before it was de-selected after much public hand-wringing, as well as concerns the art work might compromise the roof’s structural integrity. Instead, Antonakos created neon art for the inside of the Tacoma Dome.

More than 30 years later, public art at the Tacoma Dome is in the news again. A campaign is under way to place the artwork designed by the late Pop artist Andy Warhol during the early-1980s atop the Dome. In February, Tacoma City Council voted unanimously to support a campaign to raise money for the project. The estimated $5.1 million needed to see Warhol’s work crown the iconic, City-owned downtown arena will come from the private sector—not City coffers.

In my mind, Lathrop is a key reason why people are even proposing the idea of placing Warhol’s design atop the Tacoma Dome. Without One Percent for Art, $280,000 wouldn’t have been set aside for public art. And without $280,000 up for grabs, one could argue high-profile artists such as Warhol wouldn’t have considered creating original work for the Dome.

“She was bold, tenacious, persuasive, and an amazing advocate for the arts in Tacoma and Pierce County,” Greg Geissler recently told me. Geissler was active in the city’s arts scene beginning in 1975, and was hired in 1978 as what would today be the equivalent of the City of Tacoma’s Arts Administrator. Geissler, now 66 years old, is the Assistant Vice President of Development at Metropolitan State College of Denver. He pointed to a case study produced by Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government in 1987 that recaps One Percent for Art in Tacoma and cites Lathrop as the “driving force” behind the ordinance. “When the percent for art program was adopted, I don’t believe anyone envisioned an art project on the scale of the Tacoma Dome,” he added.

I recently presented this idea—without enacting One Percent for Art in 1975, perhaps there would be no Warhol for the Dome today—to City of Tacoma Arts Administrator Amy McBride as a sort of check to see if I wasn’t just creating some elevated and hagiographic interpretation of the law’s significance.

“If there wasn’t a budget of that size dedicated to public art, we wouldn’t have had a national attraction,” she told me. “And, indeed, if Warhol had never submitted a proposal, we wouldn’t have the provenance we have. But I don’t think it is only because of the funding mechanism. It was also the bold move to make the project large and visible, and to realize we had the opportunity to engage blue chip artists. It was the move to put artwork on the roof . . . that attracted the imagination of Warhol.

“A funding mechanism is just that,” she added. “It’s what people decide to do with it that makes a difference.”

Incidentally, a decade after the One Percent for Art ordinance was enacted, it was repealed following pointed public debate over Antonakos’s indoor neon designs—a chapter in the city’s history infamously known as Tacoma’s Neon Wars. Fifteen years passed before a similar ordinance was re-enacted in 2000.

I met Lathrop last month in her art-filled Fircrest home located within earshot of children playing during recess at Whittier Elementary School. Lathrop is 83 years old and retired. She has outlived two husbands and is still active in local arts. She recently advocated to move a sculpture created by Tom Morandi in the late-1970s out of storage and into a public park near Thea Foss Waterway (see “Sun King Dethroned: Can Tacoma ever appreciate this piece of public art?” Tacoma Daily Index, Feb. 5, 2014). In 2010, she received the Presidents Award from the Pierce County Arts Commission for her volunteer work at a range of local arts organizations.

“I really and truly believed in the importance of the arts,” Lathrop told me as we gathered around her dining room table for an interview. “Maybe it’s because my mother gave me a set of oil paints for Christmas when I was 10 years old. I don’t know. I have no talent.”

She added, “I keep getting offered these wonderful volunteer positions. If I’m going to be involved as a volunteer, I like to see something start and get finished. I want to see a product at the end. Even if it’s ephemeral and isn’t a chunk of bronze or a piece of glass. Maybe it’s a dance work. Maybe it’s a play—where it’s what you see and hear versus what you can touch—there’s a product at the end. It’s a nice product. It’s a beautiful product.”

Lathrop spoke to the Tacoma Daily Index at length about the early history of the One Percent for Art ordinance and its later impact on public art at the Tacoma Dome. Extended excerpts of our conversation are included in today’s edition of the newspaper.

This article is part of a larger ongoing series of profiles and oral histories that feature key people associated with the history of public art at the Tacoma Dome. The series began last week with the local architect Lyn Messenger (see “Tacoma Dome: Before Warhol’s flower, Lyn Messenger drew diamonds on the Dome,” Tacoma Daily Index, March 30, 2015). Our conversation has been edited for clarity and abridged for publication.

“It really felt like it was something that needed to be done.”

When I first went on the [Tacoma-Pierce County Civic Arts] Commission, the City of Tacoma budget was $111—and that was for postage and mailing. The Pierce County budget was nothing. We didn’t have a paid staff at that time. We were operating out of my daughter’s upstairs bedroom. I would be down at City Hall and the County-City Building all the time, but we weren’t working out of there. It was all done by volunteers except for some interns who were paid out of grant money. We never got reimbursed for gas or meetings or any of that. I look at it now and I think, I don’t know, maybe I was stupid, but it really felt like it was something that needed to be done.

So there was a commission and we went to meetings and looked at things like the freeway plantings on the corner of East 26th Street and Portland Avenue. Stuff that didn’t have anything to do with arts commissions.

“I thought it would be a great thing to have—public art.”

I was working for the NEA and I was looking at all these other communities. You go to a place like Grand Junction, Colorado, which, at that time, had a population of 35,000 people—and every corner had a public work of art on it—and you say, “Where did this all come from? How come these people have got all this and we don’t have it? Why aren’t we having this?”

Seattle had One Percent for Art and look at the things they were doing down on the waterfront. They were commissioning something constantly. They were getting something done in Seattle.

I was at a meeting in Hartford, Connecticut, and went around [looking at public art] there. Obviously, San Francisco was way ahead of us. Working for the NEA, I met a lot of people who were working with neighborhood arts commissions, especially during the first four years that I was there. When you sit down at a table that has 30 people from different parts of the country, and they talk about what they are doing in their communities and what’s going on, you feed off those ideas.

Maybe I had grandiose ideas for the City of Tacoma. I don’t know. I was born and raised here I thought it would be a great thing to have—public art.

“The ordinance passed unanimously.”

I had no experience whatsoever in writing grant applications. None. So I plagiarized everything I could lay my hands on to draft the ordinances [laughing], and got both Pierce County and the City of Tacoma to pass a One Percent for Art ordinance.

We just lobbied them. We just filled the chambers and said, “This is something you have to do.” We had a really good City Council at that time. There was Gordon Johnston, who was an architect and the mayor. Harold Moss was on the council. Denny Flannigan was always very supportive of the arts. Jack Warnick. They were all people who were very pro-arts. We needed four votes out of seven.

My husband [at the time] was in business and we used to have fund-raisers and parties and things like that. My contribution was the cooking. I gained this reputation for making bread. One of the councilmembers—I don’t remember which one—made some remark: “You can have my vote as long as you bake me a loaf of bread.” I took them seriously. I baked seven loaves of bread and took them down to the City Council meeting and presented each one with a loaf of bread before the vote was taken on the One Percent for Art ordinance. The ordinance passed unanimously.

“There’s going to finally be enough money to do something significant in terms of public art.”

A lot of us knew [the One Percent for Art ordinance] was there, that it had passed, but we hadn’t really done very much with executing any major works. A lot of us in the arts community just kept our mouths shut [when the Tacoma Dome bond was up for a public vote]. I kept my mouth shut. We just said, “OK, if this thing passes, guess what. There’s going to finally be enough money to do something significant in terms of public art.”

I wrote to the planning commission at the City of Tacoma and said that it was really important they call attention to the fact that while they are accepting bids there’s a One Percent for Art ordinance. One percent [of the budget] has to be set aside for public art at the Tacoma Dome. It was there. It was a law. It had to happen.

There was a lot of resistance to doing anything in terms of art work. I don’t think the people who proposed the Tacoma Dome bond issue and were really lobbying for it had a clue the ordinance existed. I don’t think they knew. I think they were so focused on the idea of a sports center.

“There was a lot of resistance to using anybody from the outside.”

We got a jury together. It was a pretty high-powered jury. We asked for submissions nationwide. That also created a lot of controversy because a lot of people said, “No. It should only be a local artist who does it.” There was a lot of resistance to using anybody from the outside. Now there are a lot of great artists in our community. But at that time, there just hadn’t been a lot of them that emerged who either had the capability or the know-how to take on work of that magnitude.

[Stephen] Antonakos’s proposal was selected by the jury to be put on the roof of the Dome. I don’t know why there was such opposition to it. I still don’t know. I think it was because the sports community felt it should have been using that money on the [Dome’s] interior. The line was drawn in the sand about whether [Stephen Antonakos’s] neon [art] was going to be on the roof or whether or not it was going to be something else. The City made a decision to put it on the inside, not on the outside. So the work went up on the interior. It was not well-received at all.

Then we had the Junior Olympics here. Jim McKay is on national television, and they are skating in the Tacoma Dome. He said, as the camera man points up, “Look at that beautiful artwork inside this dome. It looks almost like the compulsory figures that our skaters have to skate.” That was kind of the icing on the cake of what I would call—not revenge, exactly. They might not like it in Tacoma, but they like it everywhere else.

“They were really very effective in getting a lot of anti-arts press at that time.”

A couple guys ran for city council and they made the One Percent for Art ordinance and the proposed artwork for the Tacoma Dome their political cause. They just built up tremendous animosity against the arts community by saying, “This is a blue-collar town and we don’t need art. We need policemen. We need firemen. It’s a waste of money.” They lobbied people to write letters to the editors, and they were really very effective in getting a lot of anti-arts press at that time.

It was totally repealed.

Somebody was going to run for office and asked for my support. I said I would only support them if they reintroduced the One Percent for Art ordinance.

“I would think that after 30 years, somebody would have learned something.”

I think that the whole environment for the arts in Tacoma has changed. A lot of that had to do with getting the Museum of Glass. People suddenly recognized that [Dale] Chihuly had some value. I don’t think it really amazes me as much as it should because I would think that after 30 years, somebody would have learned something.

It’s interesting going down there. I go to the Tacoma Dome quite often for different events and find my way around by which [Antonakos] piece is where. That’s how I find which corner I’m supposed to go to.

To read the Tacoma Daily Index‘s complete and comprehensive coverage of a proposal to place Andy Warhol’s art atop the Tacoma Dome, click on the following links:

- Tacoma Daily Index Top Stories — March 2015 (Tacoma Daily Index, April 1, 2015)

- Tacoma Dome: Before Warhol’s flower, Lyn Messenger drew diamonds on the Dome (Tacoma Daily Index, March 30, 2015)

- Tacoma Daily Index Top Stories — February 2015 (Tacoma Daily Index, March 2, 2015)

- City Council vote would formally support Warhol art atop Tacoma Dome (Tacoma Daily Index, Feb. 6, 2015)

- Top Stories 2014: #1 — Warhol Tacoma Dome (Tacoma Daily Index, Dec. 31, 2014)

- ***UPDATE*** City Council committee to revisit plan for Warhol art atop Tacoma Dome (Tacoma Daily Index, Dec. 1, 2014)

- A rooftop test for Tacoma Dome Warhol flower (Tacoma Daily Index, April 22, 2014)

- Discussion continues on Warhol Tacoma Dome roof plan (Tacoma Daily Index, April 17, 2014)

Todd Matthews is editor of the Tacoma Daily Index, an award-winning journalist, and author of A Reporter At Large and Wah Mee. His journalism is collected online at wahmee.com.