Lyn Messenger has a special connection to Tacoma. A local resident and architect for nearly 50 years, Messenger was a member of the original engineering and design team that built the Tacoma Dome, one of the largest wood-domed arenas in the world. What’s more, Messenger designed the triangular, light-blue, diamond-shaped pattern that has covered the Dome’s roof since the indoor arena opened to the public on April 21, 1983.

That rooftop design could change soon.

A campaign is under way to place artwork designed by the late Pop artist Andy Warhol during the early-1980s atop the Dome. In February, Tacoma City Council voted to unanimously support a campaign to raise money for the project. The $5.1 million needed to see Warhol’s work crown the iconic downtown arena will come from the private sector—not City coffers.

If the money is raised, Messenger’s design will be history.

But Messenger isn’t too concerned.

“That kind of architect doesn’t get very far in the real world,” Messenger recently told me. I had asked him if people were aware he created the Tacoma Dome’s original rooftop design. “The firm designed it. I happened to be the point guy—I actually did design it—but my architecture doesn’t really affect me that way.”

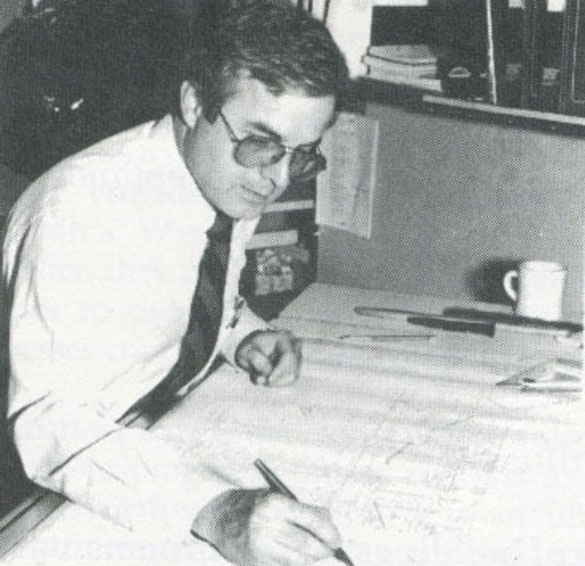

I met Messenger, 73, earlier this month in a suite of offices inside the century-old Passages Building in downtown Tacoma. He is a thin, compact man with tinted eye glasses and a short buzz cut. Semi-retired and living in Tacoma’s North End with his wife, Lynn Eisenhauer, who teaches vocal music and drama at Lincoln High School, Messenger spends his free time building sets for the school’s theater productions, and making trips down to the couple’s vacation home on the Oregon coast.

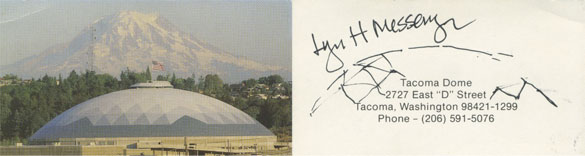

As we sat around a conference table, he offered one of the business cards (pictured below) he handed out during the early 1980s. It had a picture of the Tacoma Dome on one side, the building address on the back—a collectible, I was almost certain, for any local history buff. “I have a whole box of them at home,” he said, chuckling.

Messenger was raised on a farm in Idaho, earned a Bachelor of Architecture and Fine Arts Degree, as well as a Master’s Degree in Urban Planning, from the University of Idaho, and moved to Tacoma in 1967 after he was offered a job by the local architecture firm Johnson, Austin & Berg. In 1972, he moved over to an architecture firm led by Jim McGranahan and became a partner at the firm six years later.

In the late 1970s, support was growing to build a mini-dome near downtown Tacoma. In March 1980, Tacoma voters approved a plan to spend $28 million to build the Tacoma Dome. A team of contractors, known as the Tacoma Dome Associates, formed to handle various aspects of construction. McGranhan Architects became McGranahan, Messenger Associates: Jim McGranahan (who, incidentally, died in 2009 at the age of 73) was company president, Messenger was vice-president of design.

While the Tacoma Dome was being built, the City of Tacoma issued a call for artists to submit proposals for public art at the Dome. An ordinance created in 1975 set aside one percent of the total construction budget for public art. That meant $280,000 was up for grabs. A panel of art experts convened to attract high-profile artists and their proposals. In the end, four artists submitted plans—Stephen Antonakos, Richard Haas, George Segal, and Andy Warhol. Antonakos envisioned a roof painted cobalt blue and illuminated by neon arcs and angles. Haas imagined a cluster of stars and constellations. Warhol saw the Dome draped in a bright flower. Segal’s proposal, destined for the inside of the Dome, included statues of trapeze artists and acrobats.

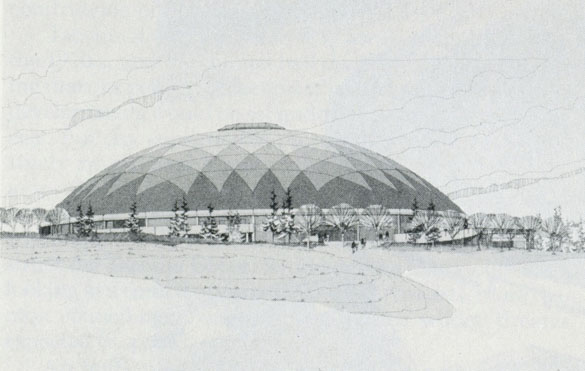

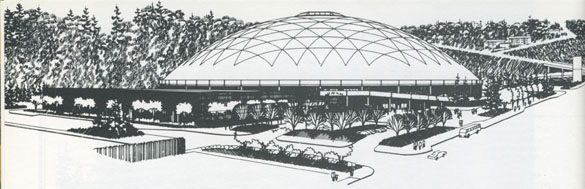

For Messenger, the roof design was only one part of the larger logistical task of building the massive arena. I would argue he never really saw the roof as a giant canvas in the same way others did. Rather, Messenger saw the Dome’s roof as a practical problem that needed to be solved. Namely, the Tacoma Dome would be huge—a 15-story, 530-foot wide bulb sitting on 68 acres just off Interstate 5. With no other high-rise buildings nearby, Messenger was concerned the Tacoma Dome would be too conspicuous.

“I guess I’m enough of an urban planner to know that something that is out of place with nothing else around to scale it would just be something out of place,” he explained.

Messenger and his team created 3-D models and mock-ups of various rooftop iterations hoping to contain the Dome’s outsized appearance. Painting the roof white just made it appear even larger than it would already be. Colorful bands looped around the building were just weird and rotund. At one point, Messenger and his team noticed the wood beams on the roof appeared fat and wide toward the base of the building, but seemed to curl and shrink as they curved upward toward the rooftop’s central point. Messenger and his team made a model that featured angled triangles that followed the curved roof beams. A fade effect was added—a darker blue at the base of the rooftop that became lighter the higher it climbed the rooftop. The design gave the building the appearance of dissolving and blending into the sky. It was a crafty, optical trick.

“People still don’t believe me when I tell them, but the apparent height was cut in half,” he explained.

Messenger told me his firm’s rooftop design was on deck while more famous artists vied for the public art commission.

“We had a model built,” Messenger recalled. “We recused ourselves from the competition because I’m enough of an artist to understand the impact that a Segal or any of them would have been [on Tacoma]. People never grasp that I would never put myself on a scale with those guys. That question was asked a lot at the time, both by my friends and other people. ‘Well, why don’t you come up with a design? A piece or art?’ We already have and it’s going to do the job it’s supposed to do.”

In the end, Antonakos’s neon design was briefly selected before it was de-selected after members of the design-build team raised concerns that holes would need to be drilled into the roof in order to install the neon. Instead, Antonakos created neon art for the inside of the Tacoma Dome.

Today, Messenger appears to be more proud of the collaborative role he played in building the Tacoma Dome, rather than the design he created for the roof.

“I don’t think people understand what it meant to the city,” Messenger explained. “It really pulled this town together. We were a hot mess. Nobody was paying attention to traffic or roads or anything else. All of a sudden, the community started talking about those things and saying, ‘That was a big project, so we can do big projects. It doesn’t need to all happen in Seattle.'”

Messenger spoke to the Tacoma Daily Index for nearly 90 minutes, and extended excerpts of our conversation are included in today’s edition of the newspaper. This article is part of a larger series of profiles and oral histories that will be published in future editions of the Tacoma Daily Index and feature key people associated with the history of public art at the Tacoma Dome. Our conversation with Messenger has been edited for clarity and abridged for publication.

“We just set up shop and became the Dome team.”

Jim [McGranahan] hired me to do renderings for a shopping center. I went down to talk to him and show him my drawings. He said, ‘This is exactly what I want. Can you do them for me for less than two-hundred dollars?’ That was a lot of money back then. Jim offered me a job the next fall.

When the Tacoma Dome started up, Jim probably thought it would be more beneficial if I actually was a partner in all of the negotiations and everything else that was going to happen. Basically, I became the project architect. I started studying athletic facilities. I went to a lot of them in about six months and learned enough about them. [We all flew down] to Flagstaff, Arizona, to look at the real thing. The Skydome was the first dome. It was a weird trip because we flew down there, landed in Las Vegas, refueled, and took off again. The pilot said, ‘This is going to be an odd sensation because we’re going to go up and we’re never going to go down.’ Flagstaff is about 11,000 feet up. We took a look at [the Skydome]. We took a lot of photos, which I was then able to transfer into real drawings.

I had three guys from my office. That’s another reason why Jim wanted a partner. He wanted someone to manage the other architects. I really liked that part of the job. I became their mentor and they became my night staff [laughing]. We just set up shop and became the Dome team.

“It wasn’t a magic[al] idea. It was just kind of a realistic approach.”

We were four months away from a presentation, so we started casting domes at scale. We started playing with what should go on the outside. Right away, we saw that white was just horrible. We had an enlarged photograph of that part of the city so we could see it from downtown, so we had a background we were shooting photos against.

We started playing with bands going around. [That was] not very successful. We did a couple versions of color where it faded. That was interesting, but not very dynamic.

One night, we all were sitting around and said, “Wait, we know what the inside does.” So we built a scale quarter-model of the trestles—or structural beam connections—out of balsa wood and placed it in a corner so it looked like you were basically seeing a whole image. When we saw it in 3-D, we saw this pattern of beams that goes from larger to smaller. We said, “That’s the answer right there.” It starts out bigger at the bottom and gets smaller at the top. People still don’t believe me when I tell them, but the apparent height was cut in half. So even though it’s the same building, when we painted it out and took a photo of it, the apparent height is cut by half.

The last thing I wanted was that bump on the freeway, that pile on the freeway. But we were pretty convinced. That’s where the diamonds came from. It wasn’t a magic[al] idea. It was just kind of a realistic approach—”How do you make a building look smaller when it is a really big building?” It was a byproduct of studying what the architecture was doing and expressing.

Marshall [Turner, President of Western Wood Structures,] really appreciated the irony of the fact that all it was were the beams underneath. But that’s important to an architect, that the structure is related. From a practical standpoint, it represents the structure inside. But it also reduces the apparent height of the building. I think it blends both from this direction [around the side] and that direction [top to bottom]. If it were all white, all you would see is all white. You would see the whole Dome at one time and it would be big. This way, it disappears in both that direction [around the side] and this direction [top to bottom]. It’s an optical illusion. I don’t know what to say beyond that [laughing].

“That roof moves. The roof breathes.”

[Stephen] Antonakos was very nice. He was really disappointed, in my opinion, that he couldn’t put [his design] on the roof. I thought [Richard Haas’s constellation] was really interesting. But why wouldn’t you do it on the inside, so that when the lights go out, it became the constellations? That was way out there. Nobody would have actually understood it because you couldn’t see it unless you were in a helicopter.

I actually liked the flower. I liked the idea of it. I’m not opposed to it being there. I think if they are going to do it on that roof, someone is going to have to come up with a product that emulates the product that’s already on there. That’s my main concern. That roof moves. The roof breathes. It goes up and down. Some people say three inches. I’ve been up on it on a hot day when I know it’s a good five or six inches higher than it is on a cold day. It swells up. That’s a huge mechanics problem and the material that we chose and had tested a lot actually moves. That material has elasticity that lets it go up and down. You need it to breathe. Even with all the fans going, the humidity rises in that building tremendously.

To read the Tacoma Daily Index‘s complete and comprehensive coverage of a proposal to place Andy Warhol’s art atop the Tacoma Dome, click on the following links:

- Tacoma Daily Index Top Stories — February 2015 (Tacoma Daily Index, March 2, 2015)

- City Council vote would formally support Warhol art atop Tacoma Dome (Tacoma Daily Index, Feb. 6, 2015)

- Top Stories 2014: #1 — Warhol Tacoma Dome (Tacoma Daily Index, Dec. 31, 2014)

- ***UPDATE*** City Council committee to revisit plan for Warhol art atop Tacoma Dome (Tacoma Daily Index, Dec. 1, 2014)

- A rooftop test for Tacoma Dome Warhol flower (Tacoma Daily Index, April 22, 2014)

- Discussion continues on Warhol Tacoma Dome roof plan (Tacoma Daily Index, April 17, 2014)

Todd Matthews is editor of the Tacoma Daily Index, an award-winning journalist, and author of A Reporter At Large and Wah Mee. His journalism is collected online at wahmee.com.