Twenty-eight years ago, Caroline Gallacci grabbed a notebook, a stack of United States Geological Survey maps, and a camera loaded with black-and-white film, and climbed behind the wheel of a Pierce County fleet vehicle. Gallacci, then a county employee, logged thousands of miles traveling to unincorporated pockets of Pierce County to compile the number of historically significant properties in the area.

“It was just me, outside, by myself,” says Gallacci, an historian and author of three books on local history, reminiscing about her work over a cup of coffee last week. “I’m amazed I survived. I encountered some interesting things. There were signs on people’s fences that read, ‘If you work for the government, don’t come in here.’ I didnt know until after I was there, but there were places around Roy where I shouldn’t have gone because there were informal shooting ranges.” Still, in many areas, long-time residents and informal historical societies helped Gallacci gather data. “People I met along the way who knew about the community would drive me around and show me places I wouldn’t have known about otherwise.”

For nearly a decade — between 1980 and 1989 — Gallacci poked around compiling the first historic resources inventory for Pierce County. “I preferred to call it a reconnaissance survey,” says Gallacci. “At the county, we didn’t have a lot of time, and we didn’t have a lot of money. It wasn’t a comprehensive survey.”

Still, Gallacci’s windshield survey is impressive.

It’s also incredibly outdated.

That Pierce County’s historic resources inventory is two decades old speaks to a concern that local historians and preservationists have held for some time. While the City of Tacoma’s historic preservation program has received necessary funding and community support, Pierce County’s program has not.

“It has been pretty much under-funded and ignored for many, many years by Pierce County,” says County Councilmember Tim Farrell, a supporter of local history groups for many years, and owner of a 120-year-old home in the North Slope Historic District. “Landmarks preservation was basically the backwater. Nobody ever paid attention to it. It was never a priority in Pierce County.”

That could change.

In early-2007, the county discovered a pool of money slated to be used for historic preservation. It accrued as a result of legislation enacted in Olympia in 2005. As of last year, the fund had collected nearly $1 million. Last November, Pierce County Council amended its budget to direct the money toward more staffing, a grant program, and a much-needed update to the inventory Gallacci completed back in the 1980s.

The infusion of money has left many within the city and county historic preservation community asking a big, but basic, question: Can Pierce County restore its historic preservation program?

‘DISMAL’ STATISTICS REFLECT A LOW PRIORITY

Gallacci’s work 25 years ago was funded by the state and led to the formation of the nine-member Pierce County Landmarks Commission. Over the years, the commission has placed 54 properties (mostly schools and homes) on its register. Ten of those properties have since been annexed to Steilacoom, which has its own historic preservation program. Today, the historic preservation program is part of the Planning and Land Services (PALS) division. Activities are reviewed by the commission about once a month.

Pierce County’s historic preservation program has been awarded two grants in its history. In 2007, it received $10,000 from the Washington State Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation (DAHP) to complete a survey of historic properties in downtown Puyallup. In 2004, it received $12,000 to survey the Home District in unincorporated Pierce County. In 2006, it applied for a $10,000 grant to create a Web site of Pierce County history, similar to HistoryLink.org, but was denied the award.

The county’s landmarks commission isn’t the busiest preservation body in the state.

Megan Duvall, coordinator of the DAHP-run Certified Local Government Program, which helps local governments with their historic preservation efforts and tracks their annual activities, provided the following statistics: between 2003 and 2007, the Pierce County landmarks commission looked at 10 properties for design review, added four properties to the local historic register (though one property was de-listed), and approved three properties for special tax valuation worth $1.5 million.

The numbers are small compared to other cities and counties in Washington State.

For example, during the same period, the City of Tacoma’s landmarks commission looked at 303 properties for design review, added 31 properties to the local register, and approved 36 properties for special tax valuation worth $50.7 million. The City also has approximately 140 properties on its register, and three historic districts (North Slope, Old City Hall, and Union Depot/Warehouse).

At the City of Spokane, which combines its preservation program with Spokane County, 107 properties were submitted for design review, 106 properties were added to the local register, and 89 properties received special tax valuation worth $39.2 million.

Local preservationists point to Pierce County’s statistics as a sign it isn’t investing enough in its program.

“This is pretty dismal stuff,” says Sharon Winters, board president of Historic Tacoma, a group that advocates for historic preservation in Tacoma. Winters requested the statistics earlier this year, and was stunned by the findings. “It’s incredibly dismal. I know there are people out there [in Pierce County] who have historic properties, and are interested in preserving them, but don’t have the support they need to actually make it happen. I know people are interested because they are calling Reuben [McKnight, City of Tacoma historic preservation officer] and they are calling me, but there’s no follow-up on it.”

Councilmember Farrell agrees.

“There are people who have approached the office and have basically been turned away,” he says. “I don’t know what happens to them either because I never see them.”

Pierce County historic preservation officer Julia Park disputes those claims, arguing that she personally responds to every request. Still, she admits, it is a tough task considering historic preservation hasn’t received the funding or priority it deserves. According to Farrell, the county spends $37,000 annually to fund the half-time preservation position held by Park, who is also a senior planner in the PALS division. The money goes wholly toward the position’s salary, and does not pay for any community outreach or other programming.

“Frankly, the county has been really into economic development,” says Park, who was joined by John Hopkins, chair of the county’s landmarks commission, during an interview last month. “Often, preserving old buildings was not a priority. It was about progress — developing new residential neighborhoods. That has been the focus of the county in the past. It has not been given the attention that’s needed because it wasn’t a priority. Councilmembers did not see an alignment of those two areas [historic preservation and economic development].”

Winters of Historic Tacoma agrees.

“My sense is that historic preservation is just not on the radar [at the Pierce County level],” she says. “There’s no conversation about historic preservation because nobody recognizes it as important. I think there needs to be an effort to raise awareness, and have individual conversations, just the way we have been doing it in Tacoma for years now. There’s not really an understanding that you would want to preserve these buildings, because it tends to be about development at the county level.”

According to Park, the program has been “hanging in there” since its inception. She notes there hasn’t been money for even basic things, like sending commissioners to conferences for training and networking. “I think they [other preservationists] would like to see a larger, better program offered by the county, which we’re starting,” she adds. “For the first time, we have substantial funding that we can begin to use. This kind of infusion of funds can only help.”

“The criticism is fair,” adds Hopkins. “It’s totally fair. But, you know, if the landmarks commission doesn’t have any money to work with, and only has part-time staff, are you going to criticize us?

“I think it’s becoming more recognized,” Hopkins adds. “And having some money helps.”

NEW FUNDING, NEW OPPORTUNITIES

The money Park and Hopkins refer to traces back to the state Legislature, and was identified in the county budget last November.

According to Pierce County Councilmember Tim Farrell, it was brought to the county’s attention in early 2007, during one of Farrell’s visits to Olympia. “It was just a casual discussion,” he recalls. “A legislator said, ‘So, what are you doing with the historic preservation fund?’ I kind of lifted my eyes and said, ‘What historic preservation fund?’ He said, ‘The one we just voted in for you guys.’ Huh?! When we checked it out, sure enough, there was the money that was sitting there and accumulating.”

It was a nice unexpected windfall — $912,000 — coming from state law that directs $1 of a $5-dollar filing fee toward general historic preservation ($342,000 has since been directed to county departments for document storage and retention, leaving $570,000 for preservation). “I talked to my [council] colleagues and we put an immediate freeze on the budget so the money wouldn’t disappear in the wind,” says Farrell. Looking ahead, the filing fee is expected to direct approximately $312,000 annually toward historic preservation in the county.

Last fall, an ad hoc committee including stakeholders from Historic Tacoma, Washington State Archives, Washington State History Museum, Tacoma Public Library, Tacoma Historical Society, Puyallup Library, City of Tacoma, county preservation officer Park, Councilmember Farrell, and other county departments, began to look at how Pierce County should spend the money. The first thing that was needed was a countywide survey of existing historical buildings, basically an update of Gallacci’s report; $366,000 of the discovered funds will be spent on this project. Another recommendation: identify historic documents within the county in danger of being discarded or destroyed, and preserve them; $60,000 will be spent in this area. Another recommendation was to develop a grant program that would distribute $200,000 annually throughout the county’s seven districts for programs aimed at historic preservation. It could include everything from bricks-and-mortar restoration to historic tours. The ad hoc committee also recommended the county turn the half-time preservation officer position into a full-time job, hire a dedicated half-time grant writer, and increase the number of landmarks commissioners from nine to eleven.

The grant program is expected to work its way through the landmarks commission and Pierce County Council approval later this spring, according to Park. Requests for grant applications will be solicited soon thereafter.

Farrell is hopeful these investments will validate the county’s preservation program and make it a priority for county council. “I think it will definitely change,” he says. “We’re going to have to take a look at where the money is going. So it will be on our radar stream.”

But is it enough?

Looking back at Pierce County’s preservation program, one question hovers: Where has the advocacy been? While other Washington State cities and counties built up their programs and actively applied for grants, Pierce County did not. Even as other department heads within Pierce County fought for more budget allocations over the years, historic preservation staff did not. Several people interviewed for this story raised one important point: on some level, making preservation important has to come from within the county itself. If there wasn’t any funding in the past, why weren’t staffers lobbying for more money, or advocating for more importance of historic preservation in Pierce County? If the county viewed it as a ‘backwater,’ why didn’t staff and commissioners try to change that perception? Even the nearly-$1-million in state funds suddenly available was discovered by accident, which is disturbing. Though there has been a monetary infusion into the program, its unclear if that translates to advocacy, and whether historic preservation is now part of the culture in Pierce County.

“If you don’t have that stream of information coming out [at the program level], then it’s not a big surprise that it wouldn’t be a priority [at the county],” says Reuben McKnight, the city’s historic preservation officer. “I think the county’s historic preservation department has to create its own awareness. If you’re not interacting with the public on a frequent basis and keeping the program relevant, then it falls off the radar. I think it’s probably not as simple as having it not be a legislative priority. While I understand it’s understaffed or under-funded, I don’t think that’s solely it. The staff and the commission and so forth have to push for these things.”

Investments that will be made this year can only help the program. But even then, McKnight has some advice for the county.

“There has to be a visible added benefit for the funding,” he says. “If you don’t have a visible added benefit, the funding could go away, and no one would complain. But if you get a windfall, and you immediately turn that into something that is used by the public, I think then it has some kind of tangible reality as being usable for people. I would say that as the program develops and they issue grants and so forth, they really need to make an effort to publicize it — both the existence of the program, and the results.”

MIDLAND’S MOMENT?

One place that could benefit from improvements in the county’s historic preservation is the unincorporated town of Midland. To be sure, blue-collar Midland is not the next North Slope Historic District. Any historic character therein needs to be explained, which is something Midland resident and community activist Stacy Emerson offered last month during a tour of the area.

Standing at the busy intersection of 99th Street and Portland Avenue, Emerson pointed to several buildings of interest: two corner gas stations with retro, drive-up overhangs (one has already been permitted for demolition); Vic’s Midland Tavern across the way by the railroad tracks appears to be saved, though it’s worse for wear (and there are whispers that when Vic passes away, the property will be sold); also near the railroad tracks sits an old feed mill (in February, the owner applied for a demolition permit). One positive sign is a pre-1940s, red brick building near the intersection. It was recently purchased by John Hemmen, former owner of The Drake on Pacific Avenue in downtown Tacoma. When I visited Hemmen last month, he was in the middle of an interior renovation, and two months away from opening a deli and coffee shop.

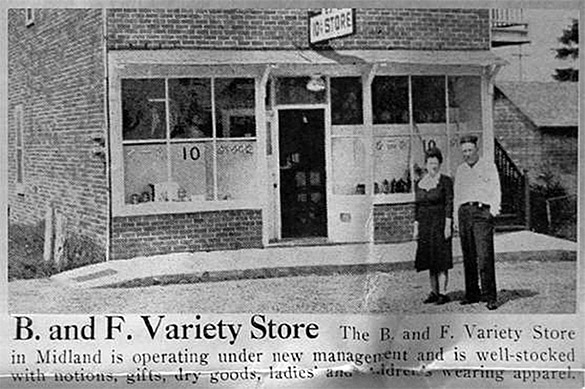

Since 2005, Emerson has wanted to add her two-story, 2,000-square-foot building to the county’s historic register. In an e-mail that has bounced around between Pierce County Councilmember Barbara Gelman, historic preservation officer Park, and Historic Tacoma’s Winters, Emerson outlines her building’s story: it’s the oldest remaining commercial building in the community, dating back to 1918 according to Assessor’s records, although community elders tell Emerson it dates back to 1916; it was a brothel, poker hall, and boxing ring during the Prohibition Era; a picture from the 1943 edition of the Midland Pointer depicts Bill and Flossy Zongas, who opened a 10-cent variety store on the ground-floor, and lived upstairs.

Emerson first learned of the building in the mid-1990s, when she leased space in the street-level floor for her frame shop. In 1997, she learned the owner was prepared to sell the building. A prospective buyer wanted to tear the building down and build anew on the vacant parcel. “This sent me into near-crazy mode,” says Emerson. “I couldn’t stand the thought of the community, and Pierce County, losing such a valuable historic asset. I begged, borrowed, and nearly stole to come up with the means to purchase it, and I have been the proud and protective owner ever since.”

Still, the building was in a sad state of repair. Soil erosion at the foundation caused the building to lean 1.5 inches. Engineers determined it would cost nearly $30,000 to stabilize the building, and another $10,000 for a long-term fix of the surface-water issue that will continue to erode the foundation.

“As far as getting my building put on a register, I felt completely discouraged,” Emerson, a community activist, told me last month. “I gave up, and I’m usually a pretty determined person.” Park provided e-mails she sent to Emerson, complete with nomination forms and ‘How-To’ tips. But that’s the extent of the county’s outreach fill out these forms, and get back to us. Though Emerson could still submit her property for designation, she won’t get the same support she would receive if the property were located in the City of Tacoma.

“Often times, I will schedule a site visit to look at the building,” says McKnight. “If there’s a group of people interested and wanting to know more, I will come out and talk to them.” In recent years, McKnight has visited residents in the West End, South Tacoma, and the Whitman area regarding their interests in creating a historic district in those neighborhoods. McKnight has also hosted nomination workshops and spoken to civic groups.

Emerson and Ed Hennings, a Midland resident and fireman with Central Pierce Fire & Rescue, have discussed opening a historical society in town. They could use the bottom-floor space of Emerson’s building, and collect artifacts and memorabilia from town elders. And perhaps Pierce County’s historic preservation program will be in full bloom by then, able to assist Midland in saving and celebrating its history.

Todd Matthews is editor of the Tacoma Daily Index and recipient of an award for Outstanding Achievement in Media from the Washington State Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation for his work covering historic preservation in Tacoma and Pierce County. He has earned four awards from the Society of Professional Journalists, including third-place honors for his feature article about the University of Washington’s Innocence Project; first-place honors for his feature article about Seattle’s bike messengers; third-place honors for his feature interview with Prison Legal News founder Paul Wright; and second-place honors for his feature article about whistle-blowers in Washington State. His work has also appeared in All About Jazz, City Arts Tacoma, Earshot Jazz, Homeland Security Today, Jazz Steps, Journal of the San Juans, Lynnwood-Mountlake Terrace Enterprise, Prison Legal News, Rain Taxi, Real Change, Seattle Business Monthly, Seattle magazine, Tablet, Washington CEO, Washington Law & Politics, and Washington Free Press. He is a graduate of the University of Washington and holds a bachelor’s degree in communications. His journalism is collected online at wahmee.com.

!["There has to be a visible added benefit for the funding," says City of Tacoma historic preservation officer Reuben McKnight. "If you don't have a visible added benefit, the funding could go away, and no one would complain. But if you get a windfall, and you immediately turn that into something that is used by the public, I think then it has some kind of tangible reality as being usable for people. I would say that as the [county's] program develops and they issue grants and so forth, they really need to make an effort to publicize it -- both the existence of the program, and the results." (PHOTO BY TODD MATTHEWS)](https://www.tacomadailyindex.com/wp-content/uploads/2008/04/pcp_reuben_mcknight-150x150.jpg)

!["My sense is that historic preservation is just not on the radar [at the Pierce County level]," says Historic Tacoma board president Sharon Winters. "There's no conversation about historic preservation because nobody recognizes it as important. I think there needs to be an effort to raise awareness, and have individual conversations, just the way we have been doing it in Tacoma for years now." (PHOTO BY TODD MATTHEWS)](https://www.tacomadailyindex.com/wp-content/uploads/2008/04/PCP_SHARON_WINTERS-150x150.jpg)

!["My sense is that historic preservation is just not on the radar [at the Pierce County level]," says Historic Tacoma board president Sharon Winters. "There's no conversation about historic preservation because nobody recognizes it as important. I think there needs to be an effort to raise awareness, and have individual conversations, just the way we have been doing it in Tacoma for years now." (PHOTO BY TODD MATTHEWS)](https://www.tacomadailyindex.com/wp-content/uploads/2008/04/PCP_SHARON_WINTERS.jpg)

!["There has to be a visible added benefit for the funding," says City of Tacoma historic preservation officer Reuben McKnight. "If you don't have a visible added benefit, the funding could go away, and no one would complain. But if you get a windfall, and you immediately turn that into something that is used by the public, I think then it has some kind of tangible reality as being usable for people. I would say that as the [county's] program develops and they issue grants and so forth, they really need to make an effort to publicize it -- both the existence of the program, and the results." (PHOTO BY TODD MATTHEWS)](https://www.tacomadailyindex.com/wp-content/uploads/2008/04/pcp_reuben_mcknight.jpg)